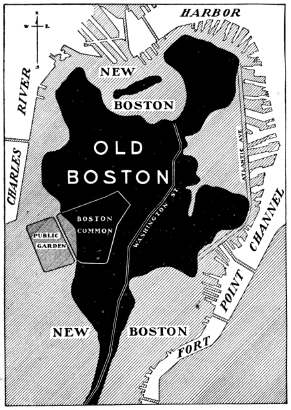

In January 2020, then Director of the Boston Planning & Development Agency Brian Golden was busy overseeing a ‘building boom’ so historic one had to cast all the way back to the days of John Winthrop for a precedent: ‘There hasn’t been this much built in a six-year sequence,’ he told Boston.com, ‘since the founding of the city in 1630.’ A heady claim for a city famously enlarged vastly beyond the 1.2 square miles of the original Shawmut Peninsula, but by the measure of ‘tens of millions of square footage in permitted development,’ probably true enough.

The ‘biggest building boom in the history of the city’ became something like Golden’s signature line: he was seeding the narrative to WBUR as early as 2015, again in a 2017 Wall Street Journal piece, in a joint Globe op-ed with Mayor Marty Walsh in 2019, and the BPDA dropped it in the second sentence of the press release announcing his resignation in 2022. Whether well-meaning boosterism, anxious overcompensation, or canny PR bluster to keep the deals flowing and the ground breaking, the breathless insistence on the bigness of the ‘boom’ seemed to gloss over something fundamental: building what, exactly?

Over a decade into the post-recession development mania, Boston has become known as much for its wildly expensive housing as its universities, sports, or tourist charms, and the ‘affordability crisis shows no sign of abating,’ per the Boston Foundation’s 2023 Greater Boston Housing Report Card. In 2022 Boston edged out San Francisco as the second costliest city for renters in the country (technically third if you count Jersey City separately from New York), and the median single-family home price in the metro area hit a record high of $910,000 this past July.

So what were the builders building? One answer is ‘luxury’ condos and apartments, an angle covered at length by the Globe Spotlight Team in ‘Reckoning with Boston’s towers of wealth,’ the third installment of its big new report on the housing crisis:

Since 2000, more than 50 sizable developments featuring multimillion-dollar condos — both new construction and renovations — have opened in Boston, according to a Globe analysis of city and state records. In a flurry of activity in the seven years from 2015 to 2021 alone, that included more than 1,000 new condos now worth $2 million and up.

Who can afford such pricey real estate? Less than 2 percent of the Boston population. Yet in the seven-year span, luxury developers built about one condo worth $2 million or more for every four such super-rich households.

Compare that to affordable housing: In the same timeframe, developers created just one affordable unit through various city programs for every 21 middle- or low-income households.

As ever, Downtown and the Back Bay claimed the most dramatic, skyline-padding projects—the Millennium Tower, One Dalton, Winthrop Center—but nowhere in the city is as closely associated with the 2010s boom era as the Seaport District. Created virtually ex nihilo beginning in the 1990s, on as blank a slate in as prime a location as there could be, the Seaport now glistens with blocks of glassy new construction often criticized as generic, confected, and placeless. (A 2019 Globe Magazine listicle slotted the ‘soulless’ neighborhood in the ‘Loathe’ column, as ‘a bland cityscape, a tract of straight lines, hard surfaces, and glass boxes,’ where ‘much of the time, you’d never even know you were near the sea.’) And with still more blocks to fill, cranes will loom for yet a while longer. In one particularly jarring case, the site of the perennially packed ‘Snowport’ Holiday Market, hosted on one of a couple open plots left in the neighborhood’s center, has for several years been approved for an 18-floor tower consisting mostly of office space.

Notably visible in aerial shots of the old, wasteland-era Seaport is the cluster of buildings on the area’s upper edge, along the Fort Point Channel. Designated the city’s ninth protected historic district in 2009, the Fort Point neighborhood had stood for well over a century, originally developed by the Boston Wharf Company from an even blanker slate than the new Seaport: the ground itself didn’t exist yet. As the Landmarks Commission Study Report explains, the company not only made the land by filling in muddy tidal flats, in a drawn-out process lasting nearly a half-century, but also designed and built the streets and eventually the industrial buildings that still stand today.

From marshy beginnings, Fort Point boomed. Summer Street became the center of the country’s wool trade, and the curved New England Confectionery Company (Necco) complex along Melcher Street ‘was the largest establishment devoted exclusively to the production of confectionery in the United States.’ The story following the Depression and WWII is a familiar one: manufacturing decline, mounting vacancy, and decades of decay until groups of artists began working and living, not strictly legally, in the high-ceilinged brick-and-beam lofts, which would gradually become again attractive to investors as the broader vision for the waterfront materialized.

Today, with the core Seaport area built up and accounted for, the largely fallow strip of land fronting the Fort Point Channel is up next. First to rise, at 15 Necco Street, is Eli Lilly’s $700 million Genetic Medicine Institute, which points to the other great gold rush of the development boom era: lab space. As Bloomberg reported in March 2022, Boston had ‘more lab space under construction than anywhere else in the U.S.,’ and was ‘poised to surpass the San Francisco Bay Area as the country’s biggest hub for life sciences.’ While the rush has since slowed, the biotech industry has already made a distinct imprint on the greater Seaport, beginning in 2011 when Vertex Pharmaceuticals announced a game-changing move from its Cambridge headquarters with a $1 billion lease of two new Fan Pier buildings. (And has kept it coming: upon completion of a new lab and office complex in 2025, ‘Vertex will occupy 1.9 million square feet of real estate in the Seaport across five sites, making it the largest biotech in Boston in terms of square footage.’)

The case of Eli Lilly in particular is rich with detail illustrating this evolution of a new economy, and perhaps even a new human. Its 15 Necco site was originally slated to be the world headquarters of General Electric, the centerpiece of a much-hyped relocation to Boston that involved a tag-team wooing effort by Mayor Walsh and Governor Charlie Baker to the tune of $145 million in tax breaks and government incentives. At the time seen as a historic coup, the deal unraveled spectacularly as the ailing industrial dinosaur imploded, shedding upwards of $200 billion in market cap over two years and eventually being removed from the Dow Jones after 111 consecutive years in the index. In 2023 the company unceremoniously packed up and left Fort Point altogether for a single floor in a tower across the channel.

Over the same period, Eli Lilly’s stock went vertical: now the most valuable drug company in the world, the WSJ reports, ‘it became the first big pharmaceutical to surpass a market capitalization of $500 billion thanks to the popularity of its obesity and diabetes medications.’ Named for a world-leading candy factory that once churned out sugar wafers and Sweethearts by the ton, Necco Street will soon host a company projected to make as much as $50 billion annually from the blockbuster drug Mounjaro (now approved to be sold as Zepbound for weight loss), a ‘GLP-1 agonist’ like its more famous cousin Ozempic. Beyond obesity and diabetes, studies are showing the potential for GLP-1s to treat heart disease, Alzheimer’s, and even substance abuse:

‘This opens up really some dramatic new opportunities in terms of control of the satiety region of the brain, but also other regions where addiction might be controlled,’ said Lawrence Tabak, principal deputy director at the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH). ‘I think these drugs are going to change the way people experience healthcare… If you are able to get a better control of obesity in this country, the savings on the back end due to reductions in cardiovascular disease, and then, you know, related conditions will be quite vast.’

And those are just the ‘traditional’ drugs. Lilly’s new Genetic Medicine Institute will significantly expand the company’s research into futuristic ‘RNA and DNA-based technologies’ that hold the potential to treat and even cure the rarest and most intractable diseases; as the company puts it, ‘The possibilities to come from genetic medicine are potentially limitless.’ In that field it’ll have some catching up to do with its Seaport neighbors. CRISPR Therapeutics opened its R&D headquarters in late 2022 in a new building a half mile away down A Street, and last week the FDA approved its sickle cell treatment developed in partnership with Vertex, the first such approval for a medicine using the groundbreaking CRISPR gene editing technique. From wool and candy to technology that promises to transform our bodies at the most elemental level—Fort Point is set for a powerful second act.

As the Lilly building approaches completion, the race to fill the adjacent land is accelerating. Next door, construction on Related Beal’s massive $1.2 billion, mixed-use Channelside project will begin soon, targeted for completion in 2026. Further down, in August the Globe reported on plans by the developer of the CRISPR headquarters to build on parking lots once used for the Gillette razor factory, and in October Proctor & Gamble announced they would fully move Gillette manufacturing operations out of the century-old site overlooking the channel. Across the water, maybe the most momentous deal of all is taking shape, as the United States Postal Service might soon enter negotiations to sell off its sprawling sorting facility property, enabling the expansion of South Station and air rights development to complement the 51-story tower currently rising above the tracks.

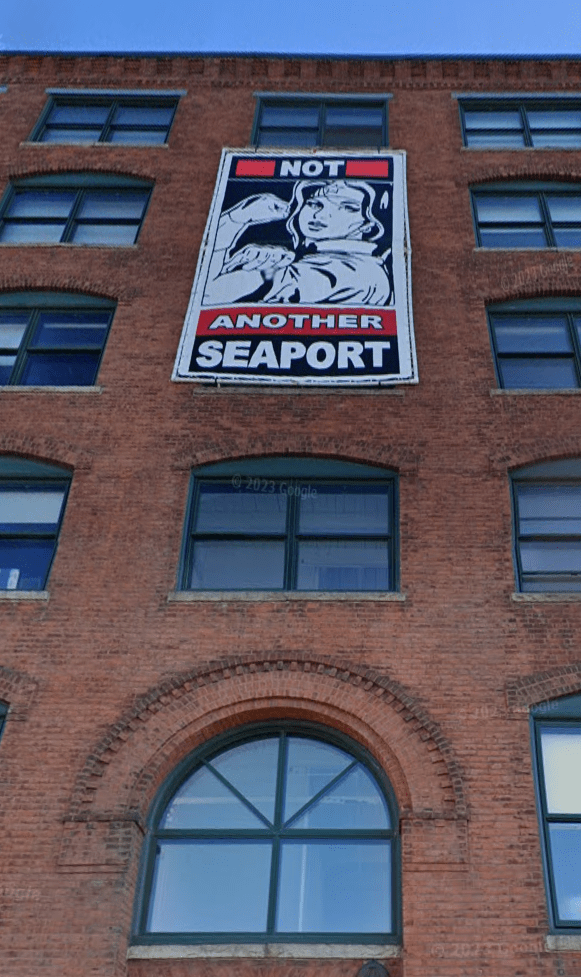

Altogether, if all goes to plan, the area surrounding the Fort Point Channel will be soon be unrecognizable, a transformation to rival the Wharf Company’s original conjuring act from the tidal flats a century and a half ago. There will be world-changing laboratories, high-powered Class A office space, and multimillion dollar residences—plus concessions for affordable housing units and ‘civic spaces’ mandated by law or leveraged via the development process—but will the result be a ‘real’ neighborhood? Not long ago, two banners hung from the 249 A Street Artists Cooperative building proclaiming, ‘WE ARE FORT POINT’ and ‘NOT ANOTHER SEAPORT’. Let us hope.

[…] The Boom, the Channel, and the New Human […]

LikeLike