Around the end of November, the Summer Street Steps in Boston’s Seaport District quietly opened for passage. Described as an ‘iconic public gathering place’ by its developer—before much, if any, public gathering has occurred—the new outdoor stairway connects Congress Street and Summer Street, unlocking a corridor between two key arteries notably separated by a 24-foot change in grade. An artifact of the Seaport’s maritime and industrial beginnings, this rift in the grid has posed a challenge to creating a cohesive streetscape in what is today a rapidly evolving area of the city.

Where Congress Street now hums with foot traffic and ground-level activity—there are several restaurants and bars, a hotel, a convenience/liquor store, a Dunkin Donuts, and three family-oriented museums—the elevated stretch of Summer Street west of the Boston Convention & Exhibition Center is by comparison barren, its only retail tenants a salon and a clinic offering botox injections and other cosmetic services. There are few options for descent, involving long walks down D Street or World Trade Center Avenue, or negotiating the somewhat treacherous sets of stairs at the A Street overpass.

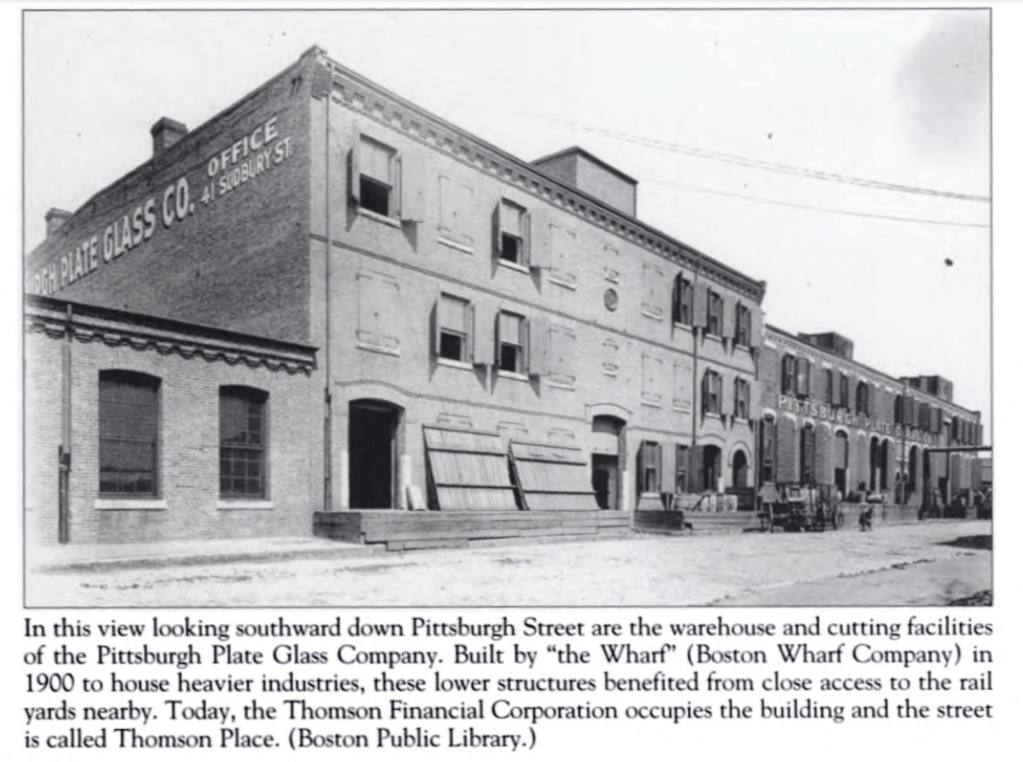

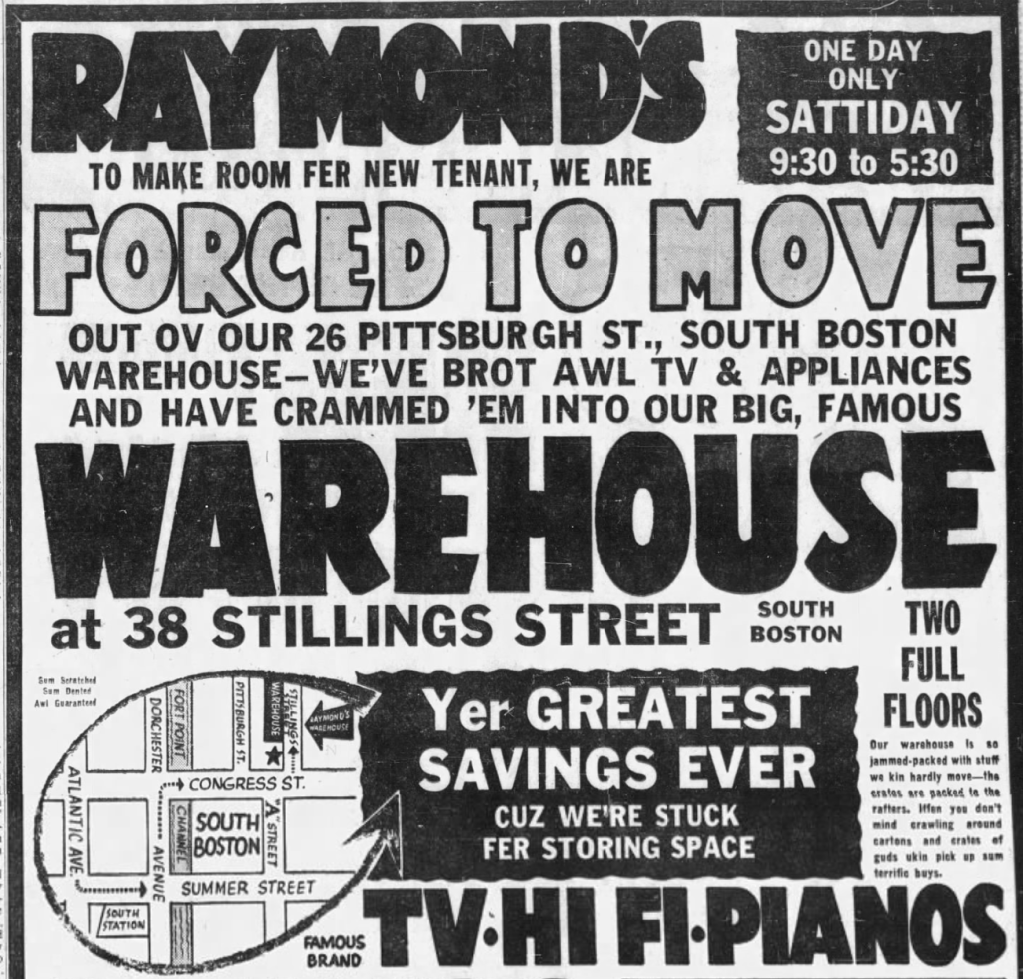

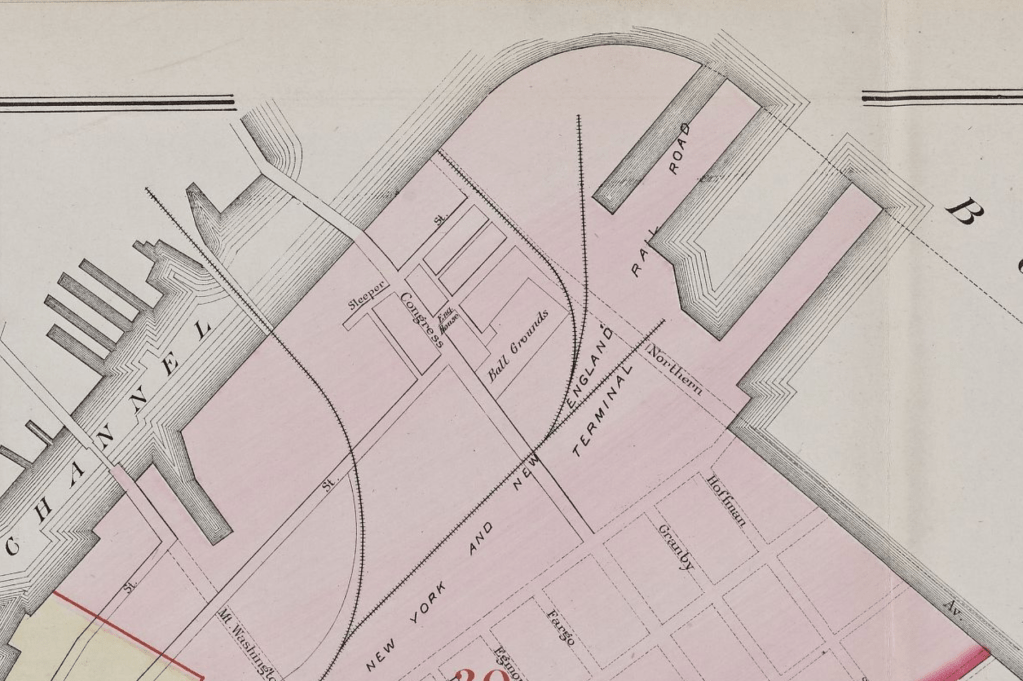

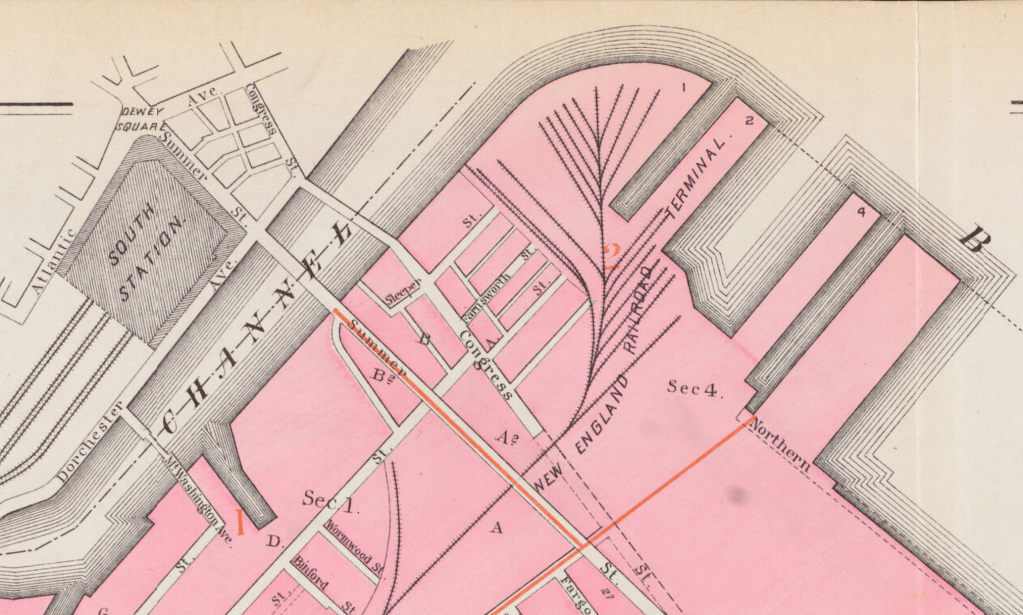

What is now an impediment was once a boon for the Boston Wharf Company and the waterfront area it created, owned, and built its signature brick warehousing and manufacturing lofts upon. ‘The pace of loft construction got a particular boost around 1900,’ the Fort Point Channel Landmark District Study Report notes, ‘when the Summer Street Bridge opened and extended Summer Street from downtown to BWCo land.’ The 1899 opening of South Station, which consolidated four separate rail terminals into one grand ‘union station,’ allowed for the removal of a railroad drawbridge that had spanned the channel near Summer Street since 1855, and helped relieve the problem of troublesome ‘grade crossings’ where trains met streets at the same level:

Even though Congress Street Bridge had been in place for over two decades, Congress Street never became an important route in South Boston. The tracks of the railroad, after 1873 owned by the New York & New England Railroad (NY & NE RR), crossed it at grade; likewise, more tracks crossed A Street at grade, separating Congress Street from BWCo’s bonded yards. Summer Street, intended to give access to the new state piers, avoided this problem by being built above grade; it ran at an elevated level through the BWCo site and continued on a viaduct over the railroad’s tracks and yards east of the BWCo land. Congress Street was then terminated at the train yards. Summer Street provided easy access between BWCo’s site and downtown, and the grade separation made it an important thoroughfare in South Boston.

Though much has changed since the days when freight lines threaded through the Seaport, Summer Street remains elevated, and an ‘important thoroughfare’ connecting South Boston to Downtown, such that it has recently become the subject of a contentious debate regarding a city plan to implement ‘a range of transportation improvements throughout the corridor.’ These include a dedicated lane for buses and trucks, and eventually bike infrastructure to extend the near quarter mile of protected lanes completed in Fort Point in 2019. The project website deems Summer Street ‘a critical missing link in existing pedestrian and bike infrastructure in the City,’ and one of the principal objectives is to make it better for walking: ‘An improved pedestrian experience will be had with the addition of transit/bike infrastructure. With improved traffic management along the corridor, pedestrians will be able to have a safer experience.’

So the Summer Street Steps are just one piece of a bigger, high-stakes puzzle. But they are an important piece, and have been touted as such since their developer presented the initial plan and renderings in 2017. How is it going so far? In one sense, it’s too early to say. The construction of the entire site isn’t complete, and the winter months aren’t the best to gauge an outdoor structure’s level of ‘activation’ as a ‘public gathering place.’ There hasn’t been much wider attention, nor a press release, though the Massachusetts NAIOP (‘the Commercial Real Estate Development Association’) did invite guests to explore the Steps as a part of their annual meeting and holiday party. An official ribbon cutting might still be years away.

In another sense, though, the Summer Street Steps are already complete by fulfilling their most basic and important function as a set of stairs: to allow for movement from up to down, or down to up. This is an accomplishment. It should be celebrated. But there is much work yet to be done, and it’s too soon to declare the project a resounding success. The first and so far only review for the Steps on Google, the listing categorized as a ‘park,’ reads:

Summer Street Steps are a game changer for commuting from Southie to Seaport! It’s now a straight shot down D Street, down the Summer Street Steps and you’re right in Seaport! The Steps even have a rail to walk your bike down the steps. And, if you have a stroller or need elevator access, you can do so right in the 400 Summer Street building.

Which is all more or less true, but if it reads like marketing copy, that’s because it is—a quick search shows the effusive reviewer is an employee of WS Development, the master developer overseeing the project.

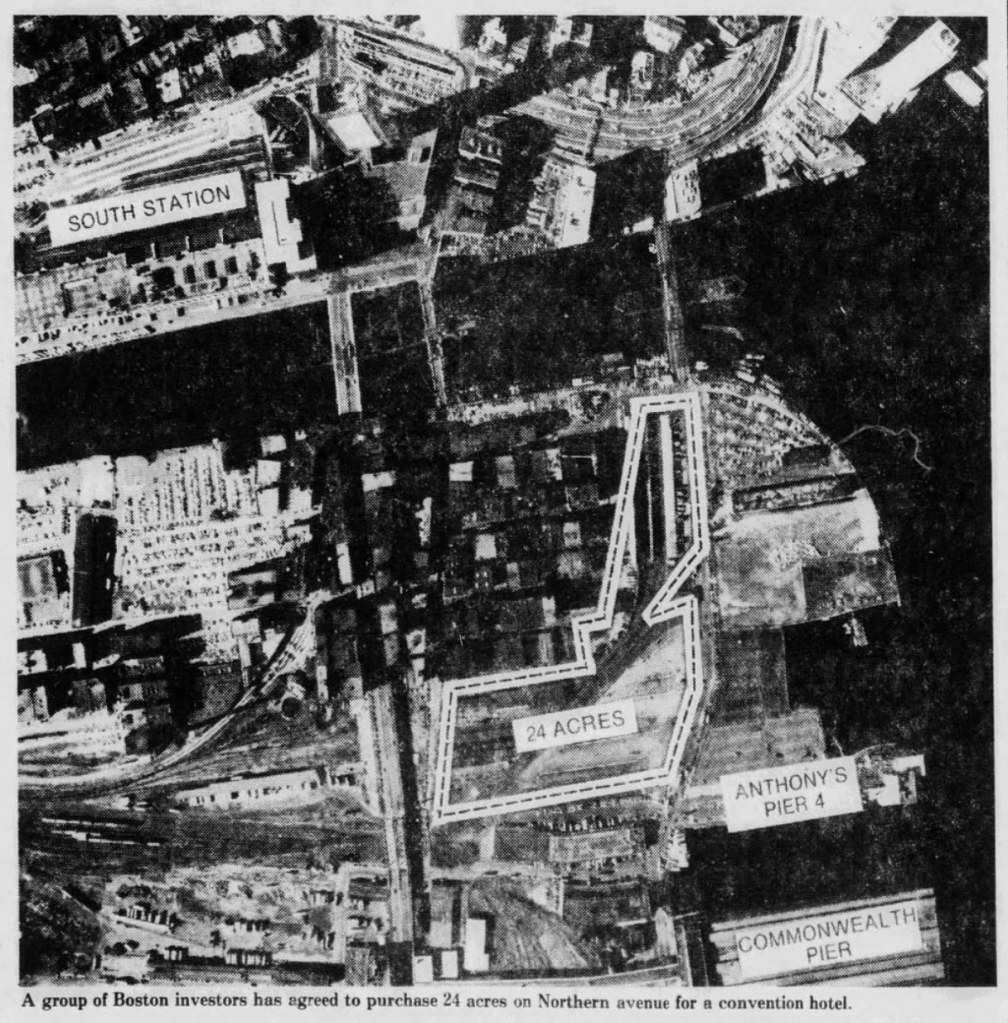

WS’s involvement in the Seaport dates back to early 2007, when it signed on as the retail partner for John B. Hynes, III and Morgan Stanley’s proposed Seaport Square development, a massive, multibillion dollar buildout of 23 acres of land at the time occupied mainly by parking lots. The provenance of the Seaport Square tract is itself a colorful, twisting saga of bankruptcies, litigation, big names, and big deals, something of a microcosm of America’s long transition to its post-industrial present, and well worth an abridged review.

J.P. Morgan’s monopoly New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad—’the New Haven’—for decades owned the freight yards terminating at Fan Pier and much of the surrounding land, and went bankrupt during the Great Depression in 1935. The company reorganized, failed again, and in 1968 was merged into the newly created Penn Central, which folded after barely two years, then the largest bankruptcy in U.S. history. Penn Central began selling off its vast real estate holdings in Massachusetts, and in 1978 a group of developers including the upstart Frank McCourt Jr. agreed to acquire the L-shaped parcel adjacent to Fan Pier for $3.5 million. They couldn’t come up with the money, and ended up selling the option on the property to the blueblood firm Cabot, Cabot & Forbes, which completed the purchase. The dogged McCourt, though, had retained an option to buy the land from CC&F, and attempted to exercise it at the last minute; they didn’t want to sell, and a lengthy legal battle between the two parties followed. A front-page Globe headline read, ‘Rivals vie to pluck a real estate plum.’

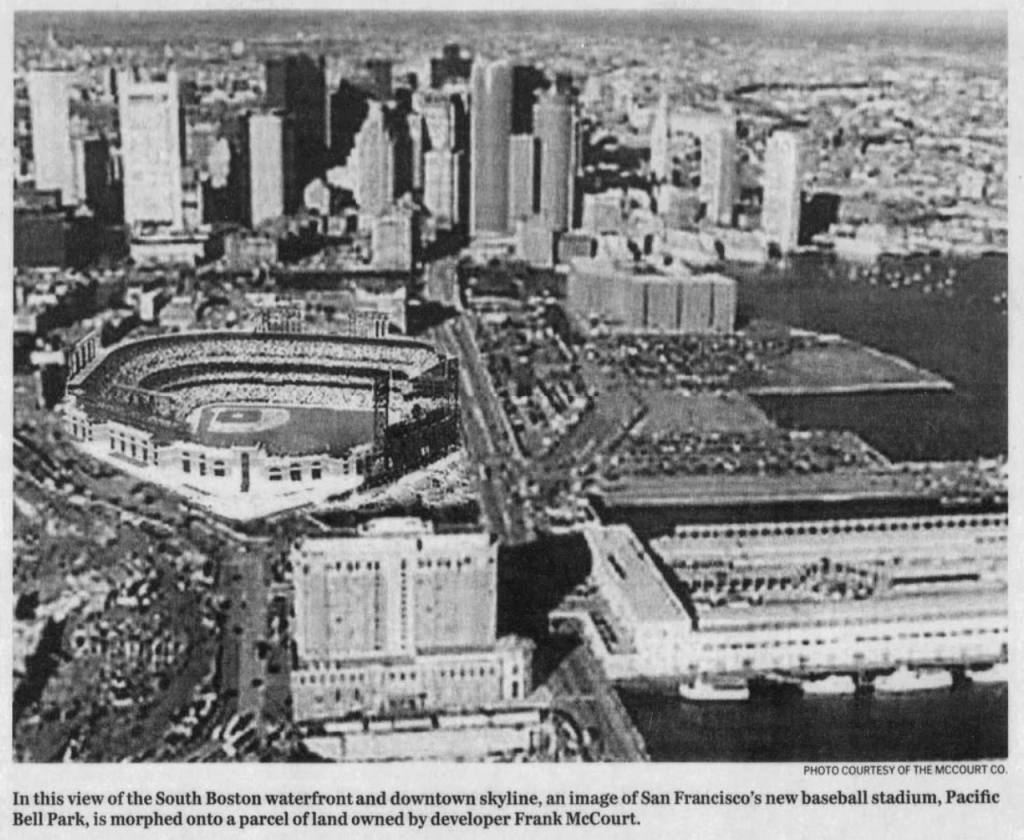

In 1987, a Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court judge ruled in McCourt’s favor, and he successfully acquired the land for $8.5 million. Over the years McCourt would present various grand development schemes to city authorities and the public, including the construction of a new waterfront stadium as part of a bid to buy the Red Sox, but none came to fruition. Economic difficulties and a strained relationship with Mayor Thomas Menino ultimately led McCourt to look westward instead, and in 2003 he leveraged his prized parcel as collateral to finance a purchase of the Los Angeles Dodgers from Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp.

When the $145 million loan came due a few years later, McCourt turned over the Seaport land to News Corp, which quickly flipped it to John Hynes and Morgan Stanley for $204 million. The deals would keep flowing as the 23-acre spread was carved up: a few plots sold to Swedish construction giant Skanska here, a couple others to Pasadena private equity firm Cottonwood Management there. WS Development acquired the remaining 12.5 acres from Hynes’s Boston Global Investors and Morgan Stanley for $359 million in 2015. A Boston Business Journal analysis found the total purchase price across all the land sales since from 2011 to 2015 had reached $665 million.

When WS Development first entered the Seaport in 2007, it was still mainly known for building suburban shopping plazas. A 1995 Globe article described it as a ‘real estate firm that often acquires sites for Wal-Mart.’ Its profile rose with the 2009 opening of Legacy Place in Dedham, which became an instant success by putting forward a new vision of outdoor-oriented, ‘lifestyle center’ retail, contra to the prevailing style of enclosed, big-box-anchored malls like those in Burlington and Natick. As ‘a new type of mixed-use retail district and an embodiment of New Urbanism,’ the design firm Prellwitz Chilinski says, ‘Legacy Place captures the appeal of a town-like pedestrian experience, offering a lively, people-friendly streetscape with landscaping and exterior cafés suggesting a neighborhood that grew over time.’

This more thoughtful ‘approach to placemaking’ can be commended, but there are only so many ways to innovate fundamentally retail-oriented spaces. If the new Seaport can often feel like a high-end, harborside mall, well, it’s in the developer’s DNA. Inducements to shopping are highly visible throughout WS’s properties. See, for example, the banner on a temporary construction wall across from the bottom of the Summer Street Steps, as work on the connecting ‘Harbor Way’ path continues: ‘This way to more shops,’ it beckons, beside a busy grid of brand logos.

The single strangest feature of the Steps likewise seems to be borrowed from the retail playbook. There are five large, green JBL speakers deployed in a zigzag down the tiered landings, playing a Spotify Today’s Top Hits-type selection of songs at moderate volume apparently around the clock. From the entrance to ‘Harbor Way’ at Autumn Lane through where it currently lets out at Pier 4 Boulevard, there is also a constant stream of pop music. This is fine, maybe even pleasant if you happen to catch a favorite tune, but it doesn’t help dispel the sensation of walking through a shopping center.

What about the rest of the Steps? There are nice design touches: the central wooden boardwalk, and the emphasis on the raised planters and trees, which when lush and blooming will make the location an attractive oasis in a neighborhood sorely lacking green space. Lights at night add warmth to an eerie and canyon-like area bracketed by construction sites. There is a tiny, almost unnoticeable dab of a harbor view from the top of the stairs, but it may be seasonally obscured when the project is complete and the leaves of the Harbor Way trees come in.

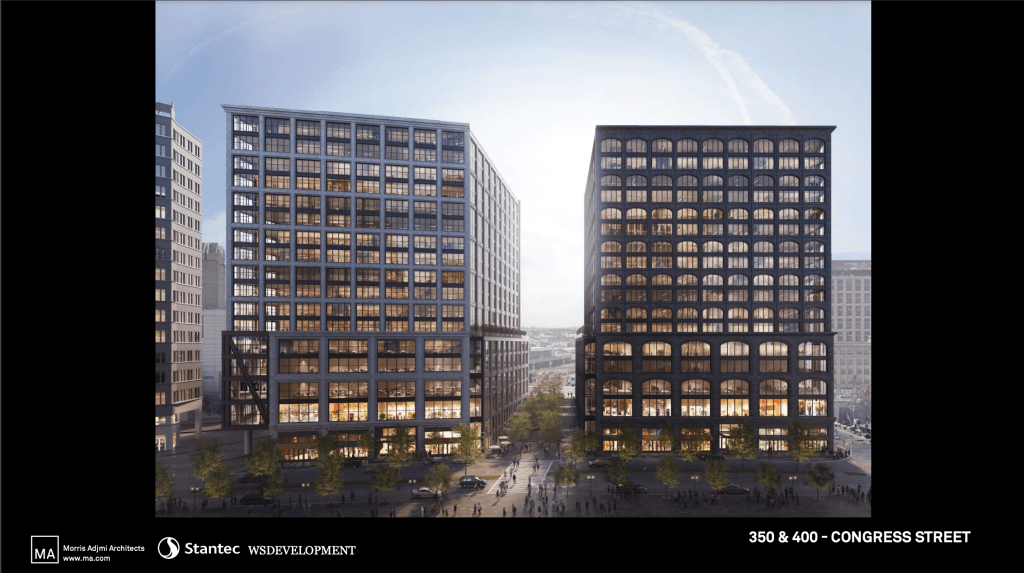

The more interesting view is actually looking west, down Congress Street, the Wharf Co. lofts in the foreground and International Place looming behind, but this is only temporary. The Steps opened along with the adjacent 350 Summer Street office tower, home to Roche-owned ‘molecular insights company’ Foundation Medicine, and its companion building 400 Summer Street is due to rise on the other side. Construction hasn’t yet begun, and this past October WS asked for an extension on its permit from the Boston Conservation Commission, claiming that ‘global economic conditions and the office and laboratory leasing market have changed dramatically, impacting [their] ability to finance and lease’ the tower. In January the Wall Street Journal reported that office space vacancy in major U.S. cities had hit 19.7%, the highest figure since the data began being tracked in 1979, and a follow-up story warned that ‘even premier towers are starting to wobble.’

350 Summer’s prime location alone, with Amazon moving in across the street and a number of blue-chip biotech, consulting, and law firms nearby, should ensure WS will find a tenant eventually. But there is a certain irony to the plea for more time. The block was initially permitted for 350,000 square feet of residential space, until WS filed in 2019 to change the building use to ‘office and/or research and development.’

Basic features of the Summer Street Steps have also changed, or are yet to materialize. As the Fort Pointer has documented over the past several years, the initial renderings of the Steps in 2017 presented a rather grander picture. Sure, the project isn’t finished, it’s the middle of winter, and plans evolve. Still, the site simply looked far more spacious and impressive in the original images than it is in reality.

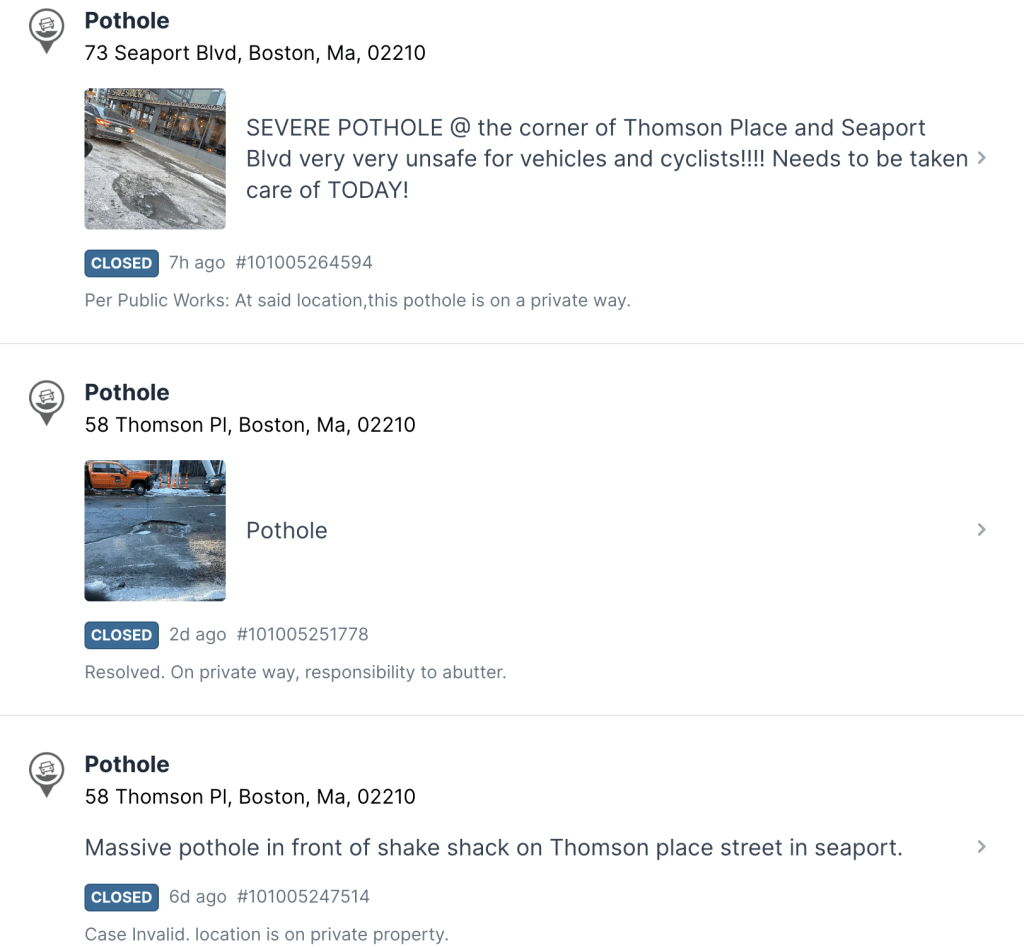

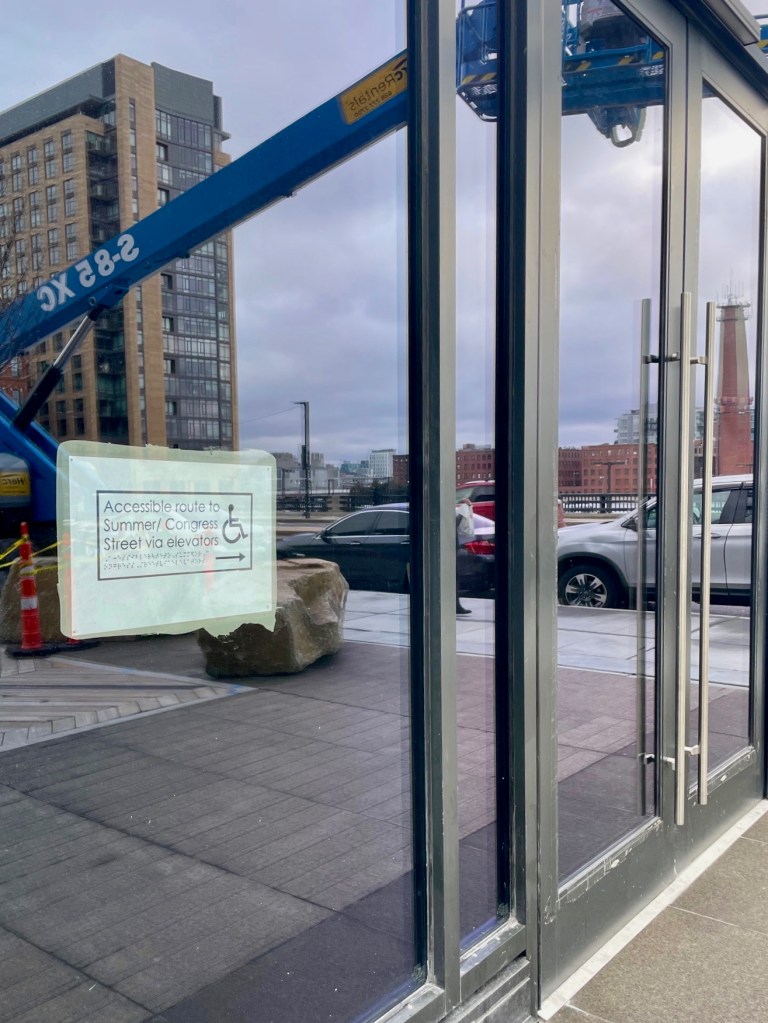

For such a large, blank canvas, accessibility hasn’t been granted the utmost consideration. In a 2017 comment letter, the waterfront advocacy group Boston Harbor Now strongly encouraged taking a holistic approach to mobility at the location, ‘incorporating a combined ramp and stairs design’ to ‘promote an equal experience for all users.’ Instead, the Boston Planning & Development Agency settled for a commitment from the developer to ‘install a public elevator in close proximity to the Summer Steps and outside of the building’s structural core.’ Currently the elevator route is not immediately adjacent, nor prominently called out, and on either level involves walking three doors down into and through the lobby of Foundation’s office. WS’s Notice of Project Change document submitted to the BPDA in February 2017 said, ‘The experience and design quality of this route will be similar to that of the Summer Street Steps and it is intended that the public would not need to enter into traditionally privatized space such as a residential or office building lobby in order to access this critical accessibility pathway.’

That is a particularly flagrant dereliction; other aesthetic criticisms may seem like trivial sideline quibbling. Building anything in Boston, let alone two thoughtfully designed and historically-informed towers bearing public benefits, is hard enough. The obstacles are numerous. Large sums must be raised, bureaucracy navigated, abutting interests placated, tenants signed. But surely we can do better than ‘take what you can get.’ Billions of dollars of public money—the harbor cleanup, Big Dig, Silver Line, courthouse, convention center—went into making the Seaport a viable arena for private development. Powerful companies and illustrious families fought for decades to build on the waterfront, because everyone knew such an unparalleled opportunity would likely never come around again. The moment demanded more than Class A+ office space and nice stores.

The Summer Street Steps at least are not solely that. They serve a valuable purpose, and years from now could even be fondly seen as the ‘iconic public gathering place’ that has been promised. Stairways are potent symbolic structures, and in the best cases can define and elevate a space to sublime heights. In the original 2017 project plan, WS described their work as being ‘modeled conceptually on the Spanish Steps in Rome and other monumental stairs around the world.’ If only the execution were as ambitious as the vision: the Summer Street Steps are fine, but a Baroque masterpiece they are not.