In January, a month out from Super Bowl LVIII, Ad Age reported ‘a modern-day record number of candy and sweets brands advertising’ during the game, a noteworthy development given the $7 million price tag for each 30-second spot. Beyond a general rise in marketing spend across the category, and an opportunity to target younger viewers via the game’s zany Nickelodeon simulcast, consumer research experts and brand leaders pointed to more fraught psychological and cultural factors driving the commercials. ‘There’s the feeling of, “The world was nicer when I was younger” and people want to indulge in that,’ theorized a senior director for market intelligence firm Mintel. ‘We are heading into an interesting year—there are wars, conflicts, return to work policies, and an election year,’ her colleague continued. ‘That’s a lot of stressors. But the Super Bowl would be a prime time to remind consumers those treats are here.’ The VP of Oreo U.S. promised that ‘fans can expect the cookie brand to continue to find unexpected ways to alleviate the seriousness of adulthood.’

Whether or not Oreos can really take the edge off geopolitical carnage and domestic strife, the idea isn’t as fanciful as it sounds. Sweetness can stir powerful feelings of nostalgia and comfort, a fact novelists and marketers alike know well. Proust’s crumbly madeleine dipped in tea unleashes a stream of memories that flows for thousands of pages. In Don Draper’s pitch to Hershey executives—the fantasy version before he reveals his upbringing as an orphan in a brothel—the iconic chocolate bar is ‘the currency of affection. It’s the childhood symbol of love.’ Mintel research found that 76% of UK consumers are ‘attracted to sweets that remind them of their childhood,’ and the same percentage of US consumers ‘use sugar and gum confectionery as a mood improver.’ According to the CEO of the National Confectioners Association, ‘Seasonal treating is deeply rooted in tradition and elicits memories of happy times, sharing with loved ones and an unmatched feeling of nostalgia.’

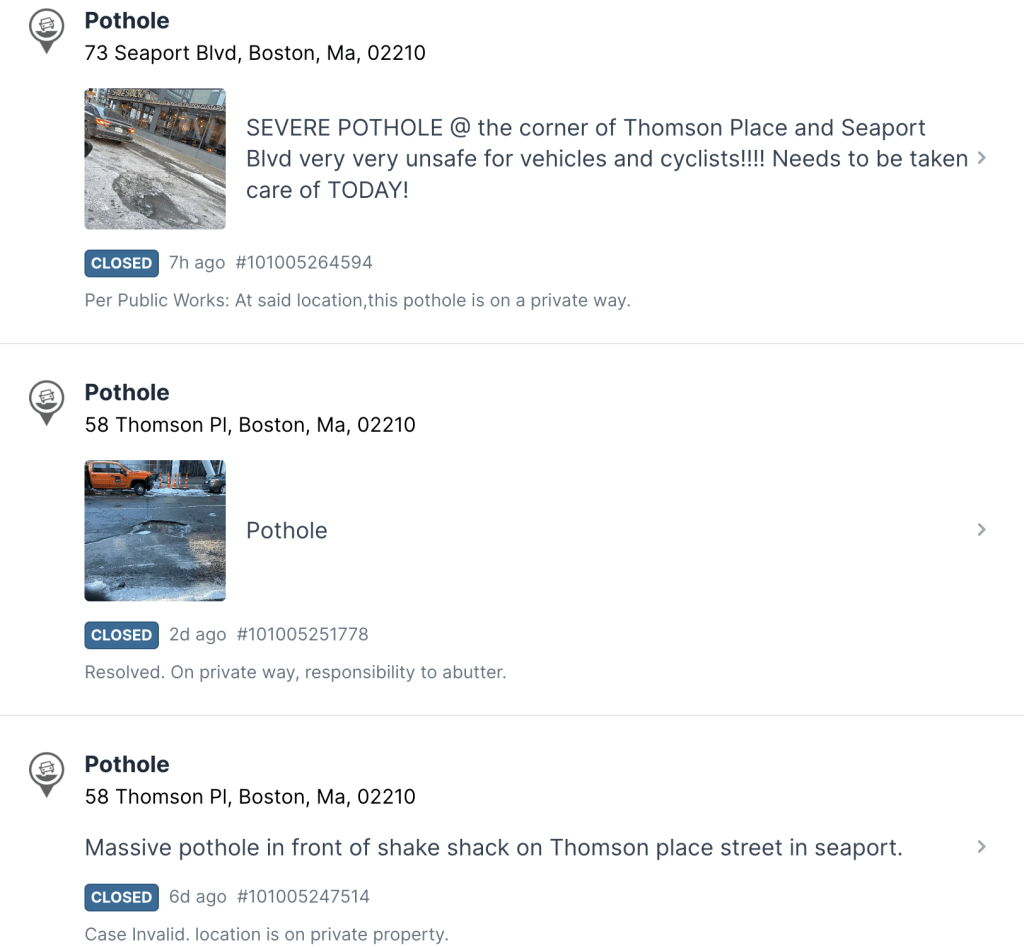

Retro treat vendors in particular deal explicitly in the remembrance of things past—OldTimeCandy.com has trademarked the tagline ‘Candy you ate as a kid!’—and few brands have been as wrapped up in their throwback appeal as those of the once-eminent New England Confectionery Company. The longest operating candy manufacturer in the United States until its messy demise in 2018, Necco produced its flagship multicolored sugar wafers, conversation hearts, and other sweets for over 150 years in a series of factories in and around Boston, but after World War II it struggled to sustain a lasting hit on the level of the marquee bars of Hershey and Mars. Unusual for a candy product, Necco’s signature creation eventually became known for not tasting particularly good at all: a Wall Street Journal headline around the time of the company’s meltdown read, ‘For Candy Fans, the Only Thing Worse Than Necco Wafers Is No Necco Wafers.’ The wafers’ charm is in their longevity as chalky tokens of vintage Americana, that they have been around since before the Civil War and haven’t much changed, except for a brief period when Necco executives sought to please the ‘modern, health-conscious consumer’ by swapping out artificial ingredients for ‘more expensive natural flavors and colors derived from red beet juice, purple cabbage, cocoa powder, paprika, and turmeric.’ Wafer sales tanked 35 percent, and the original formula returned less than two years later. The company had misunderstood the whole point of its namesake offering.

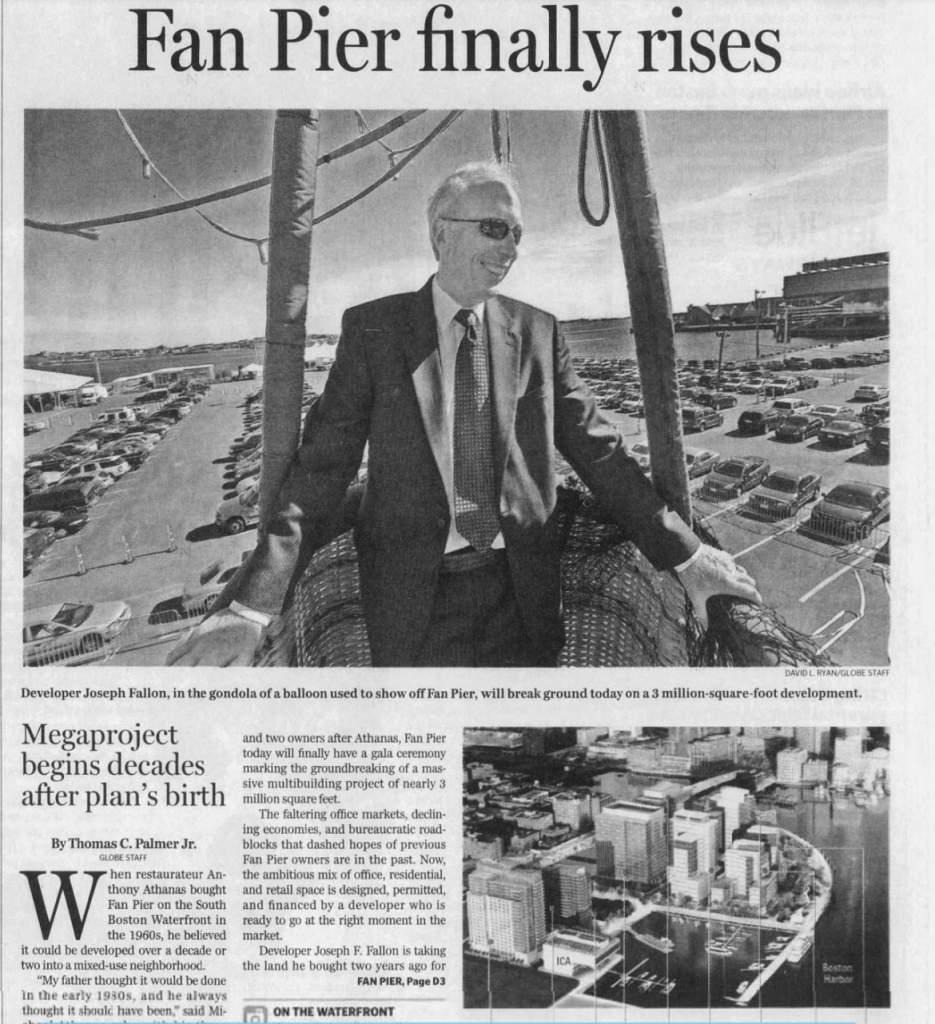

The recipe debacle might have been overcome, but by then Necco was already on its way to a chaotic dismantling at the hands of profiteering private equity firms. In 2007 American Capital Strategies (ACAS) acquired the company in a leveraged buyout and split it into two separate entities, one holding Necco’s real estate and the other running the confectionery business. After ACAS was itself acquired by Ares Management in 2017, the merged firms proceeded to sell Necco’s most valuable asset, its recently built 50-acre factory in Revere, for nearly $55 million, and the candy maker filed for bankruptcy a year later. A lawsuit filed by Necco’s bankruptcy trustee charged ACAS and Ares with ‘misconduct and manipulation’ of the company, spiking a deal that would have given Necco a chance to continue operating so that the firms could extract maximum gain for themselves:

In sum, the sale of the Revere Property enriched Ares/ACAS by approximately $54,700,000 but left NECCO Candy in a dire position in which it was incurring rent expenses it could not afford, receiving zero additional funds to operate an already struggling business and being required to vacate its facility, without any financial ability to fund the cost of relocation. As a result of the sale of NECCO Realty, the only option available to NECCO Candy was a liquidation.

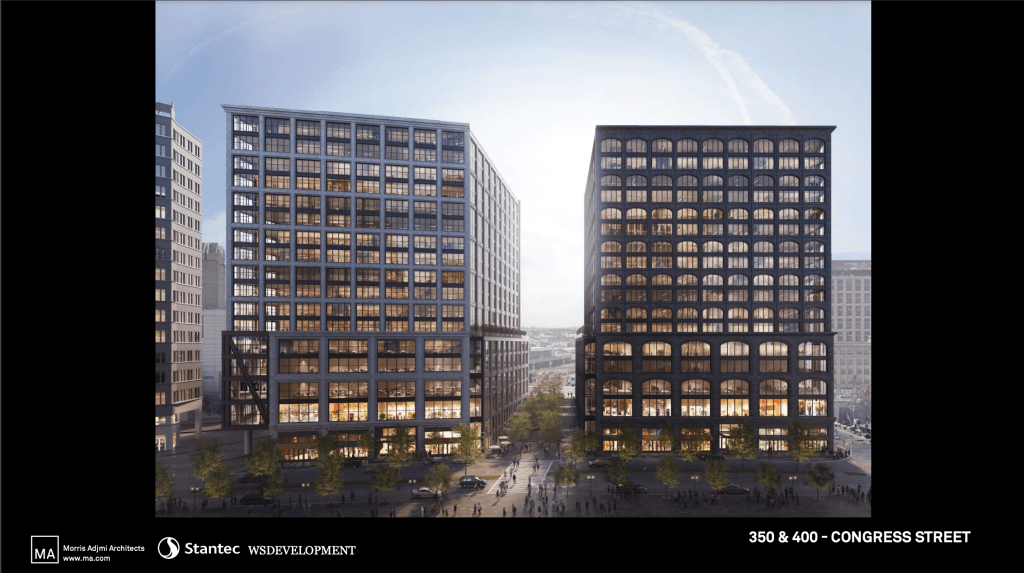

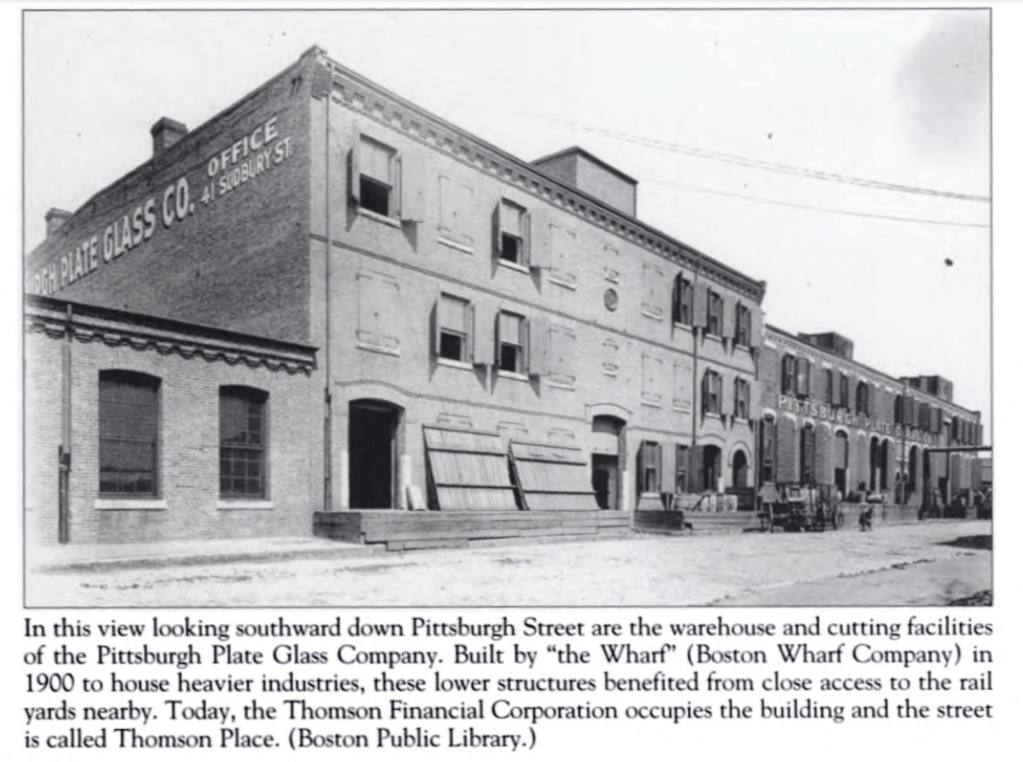

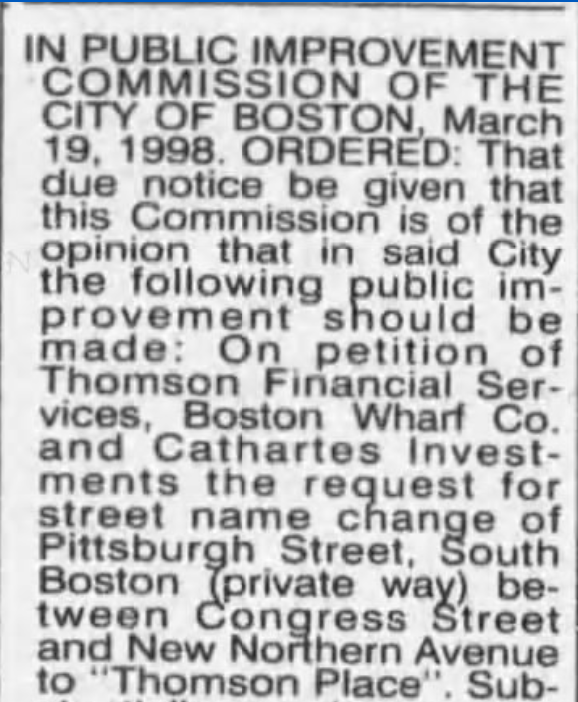

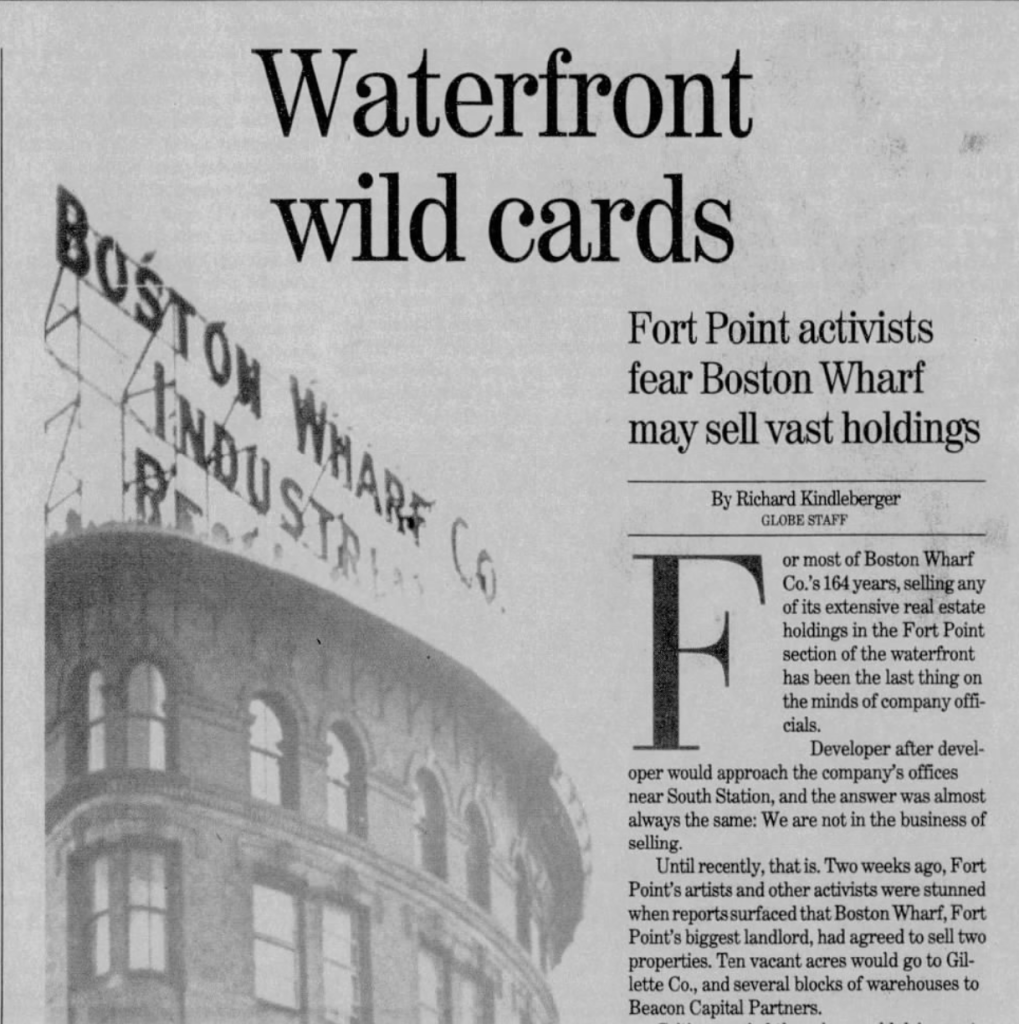

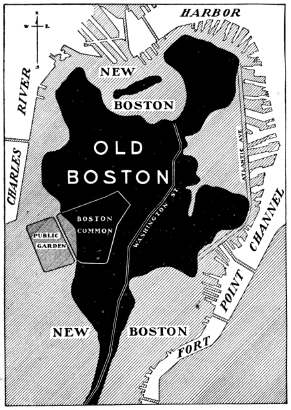

The saga served as a bitter reminder that no business, no matter how sweet and whimsical its product, is immune to the unsavory machinations of high finance. Necco’s main brands were auctioned off to other confectioners to carry on production, but the bankruptcy proceedings marked the end of a venerable institution that dated back to 1847 with apothecary Oliver Chase’s invention of the first candy-making machine. The New England Confectionery Company was incorporated in 1901 via the consolidation of Chase & Co. and two other leading Boston candy firms, and the following year moved into a large manufacturing complex along the Fort Point Channel built for the new combine by the Boston Wharf Company. Aside from its place in the annals of sugar lore, Necco’s architectural legacy may end up its most enduring: the Cambridge factory it moved to in 1927 is listed in the U.S. National Register of Historic Places, and the Revere site was ultimately sold again for $355 million because of its newfound use as an Amazon fulfillment center. In a sign of the times, since 2018 Amazon has also occupied the first Necco factory in Fort Point as corporate office space.

With its imposing chimney, prominent frontage on the channel, and a curving, yellow-brick facade along Melcher Street, the original Necco complex may be the most distinctive set of buildings in a neighborhood cherished for its grand old lofts. Histories of Fort Point begin with the filling of the area’s shallow tidal flats by the Boston Wharf Company in the mid-nineteenth century, and note the land’s initial use for sugar and molasses storage sheds, but they have perhaps undersold just how important the sugar business was to the creation and evolution of the district. They don’t pause to tease out the darker implications of what was for centuries a brutally lucrative trade built on the labor of enslaved millions. While Fort Point would indeed serve a broad range of commercial uses, sugar provided the impetus and a chief source of capital for the Boston Wharf Company’s landmaking and later pivot to real estate development, and as industrial activity in the area generally declined, large-scale sugar refining lasted well into the twentieth century. One powerful Massachusetts merchant family played a central role in all of it.

The Atkinses of Truro, later Belmont, trace their lineage almost all the way back to the beginning—family historian Helen Atkins Claflin records their earliest American ancestor’s arrival in Plymouth in 1639—but they didn’t accumulate much wealth or renown for five or so generations. All that’s written about one Samuel Atkins, who lived through the Revolutionary War, is that he ‘made his living from fishing and farming.’ That began to change with Samuel’s son Joshua, who found success as a sailor and merchant shipowner plying the ‘West Indies trade,’ something of a euphemism for the traffic in tropical commodities produced by the slave colonies of the great European powers. New England merchants had prospered enormously from the famous ‘triangle trade’ for over a century before Atkins got involved; lacking a hinterland full of precious metals or farmland able to support a plantation economy, colonial Boston had to look seaward to sustain its tenuous position far from the motherland. ‘But the challenge of survival,’ Mark Peterson writes in The City-State of Boston, ‘pushed the infant colony into a fatal bargain: an economic alliance with the sugar islands of the West Indies. This effectively made Boston a slave society, but one where most of the enslaved labor toiled elsewhere, sustaining the illusion of Boston in New England as an inclusive republic devoted to the common good.’

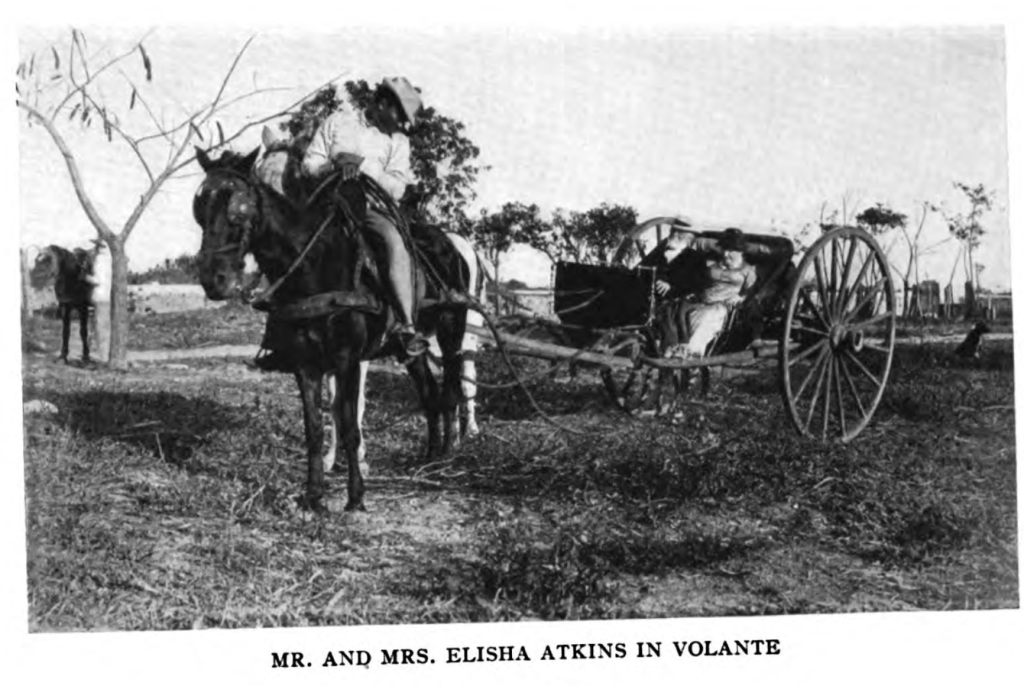

Joshua Atkins made a trading voyage to Cuba in 1806, ‘bringing back as cargo hides, sugar, and molasses,’ the earliest record of the family’s presence there, but the extent and nature of their involvement around this time is murky. Joshua’s son Elisha Atkins would formalize an ongoing, high-volume business in Cuban sugar beginning in the late 1830s, but according to historian Stephen Chambers, the family’s ‘true start in Cuba, like that of many elite New Englanders, began with the illegal slave trade, in a commercial house at the Cuban port of Matanzas, under the leadership of Zachariah Atkins, where he worked since at least 1808.’ There are few extant archival records of Zachariah Atkins, and no genealogy detailing his relation to the other Atkinses, but his name appears in British Foreign State Papers regarding the 1822 seizure of the ship Joseph, which ‘Was employed at the time of Capture in carrying on the Slave Trade for the account of one Zachariah Atkins, resident at Matanzas, in the Island of Cuba.’ Neither Elisha Atkins’s biographer nor Helen Atkins Claflin make any reference to a Zachariah, but it seems plausible that the family may have been unaware of or disinclined to note an ancestor’s direct participation in the most heinous and reviled of businesses. In any event, the later, more famous Atkinses’ relation to Cuban slavery is rather less ambiguous.

In 1838 Elisha Atkins established a partnership with the son of William Freeman, a prominent Boston merchant who set the pair up with three of his trading vessels and loans of $2,500 each. Freeman Sr. had close ties to Cuba—his brother and son had both lived there, engaged in the sugar trade—and helped found the Boston Wharf Company in 1836, serving as one of its original directors and later president for 16 years. Elisha Atkins married Freeman’s daughter in 1844, around the time he had begun making regular voyages to Cuba; in an 1843 letter to his then-fiancée, Atkins wrote of his reception at a plantation near Trinidad, a significant center of sugar production:

We were treated with much attention by the major-domo, who opened the house for us, got us a fine supper, and furnished us with cots. Here we slept, the sole occupants of the house, surrounded by about three hundred and fifty negroes, and perhaps but three or four white men on the place; but so perfect is the subordination that you feel perfectly secure. But if ever they learn their strength, woe to the white population! The estate of which I speak is situated in a beautiful valley which extends many leagues into the interior, the whole of which is occupied by plantations all highly cultivated, three of which we had passed over, with three to four hundred negroes on each, and around us, within sound of the report of a cannon, lay some two thousand slaves, among whom were perhaps not thirty white men. There was, to be sure, a small guard of soldiers in this neighborhood. Yet there are to be found persons who are anxious to sow among the negroes the seeds of discontent, and by showing them their situation excite them to rebellion. . .

The sense of paranoia is palpable: Atkins fixates on how outnumbered he and the other ‘white men’ are, and seems to waver in his certainty of how ‘perfect’ the ‘subordination’ really is or might remain. Like many New Englanders who profited from slavery, whether in the American South or the Caribbean, Atkins could apparently tolerate the practice itself, but not the transport and sale of human beings that made it possible. In the same letter, on witnessing the landing of a slaving vessel, Atkins remarks, ‘This revolting traffic, the slave-trade, is still far from extinguished.’ Although Britain had abolished the ‘revolting traffic’ throughout its empire in 1807, ‘it struggled to contain the Atlantic slave trade in Cuba and Brazil,’ Ulbe Bosma writes in The World of Sugar, and ‘Cuba emerged as the world’s largest sugar exporter through massive importation of enslaved Africans.’ Bosma cites figures that ‘suggest that at least 332,800 enslaved arrived between 1835 and 1864,’ the period when Atkins cemented his company’s status as one of the leading dealers of Cuban sugar.

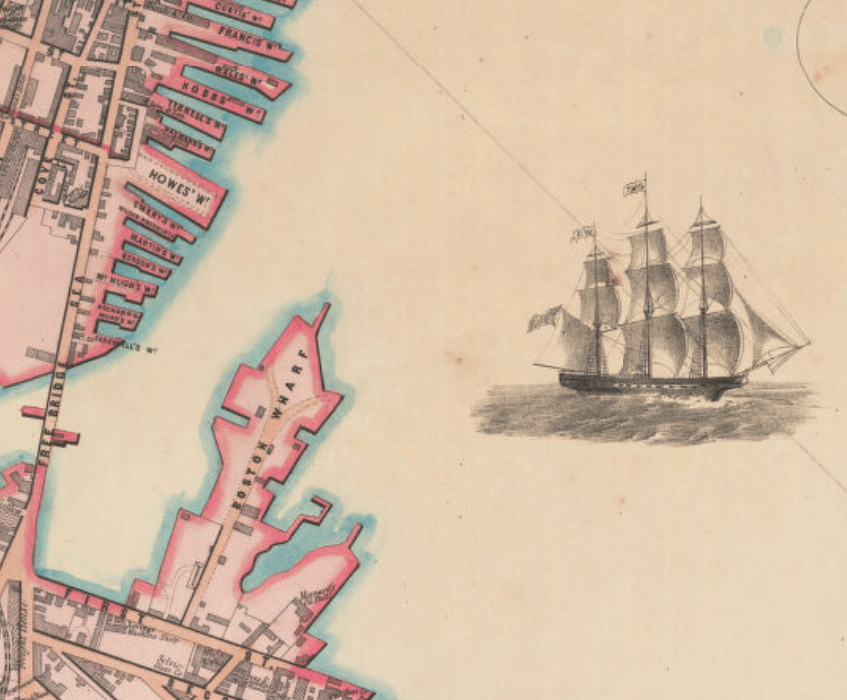

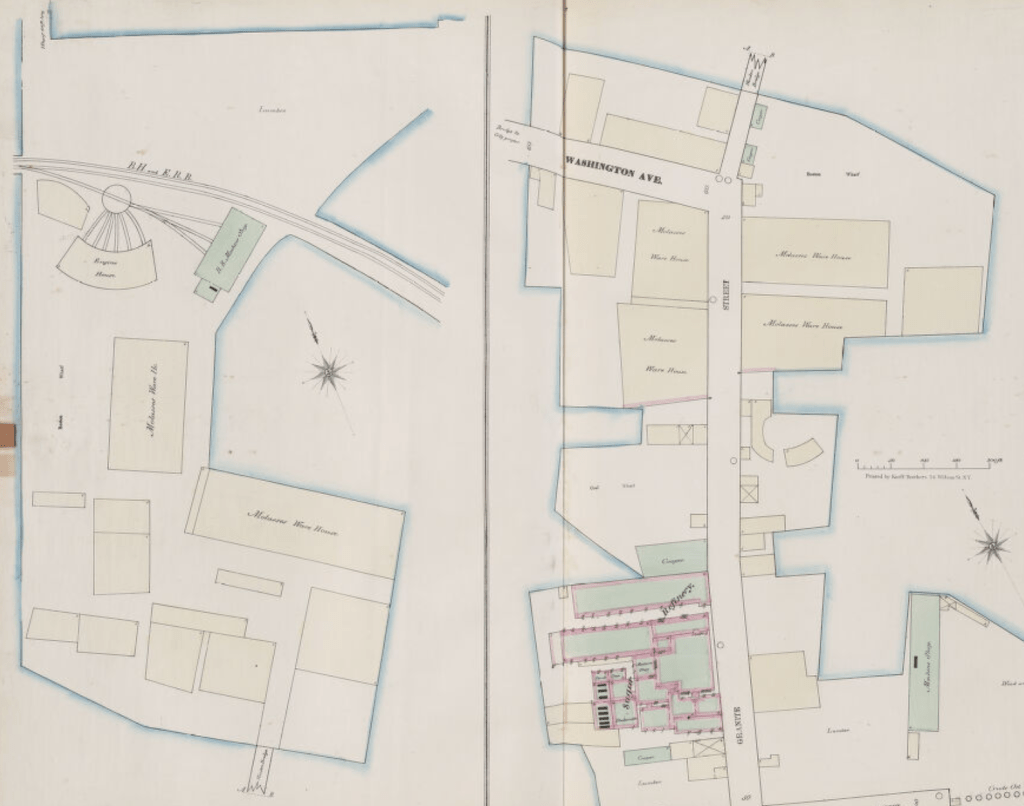

Back home, Atkins became a shareholder and director of the Boston Wharf Company in 1849, when the venture was still in the early stages of what would over the next several decades become a massive landmaking operation. According to his biographer, from then on Atkins ‘gave constant attention to the development of the company,’ steering it as it overcame persistent opposition from rival property owners and the Commonwealth of Massachusetts itself. Atkins ‘was never prominent in these controversies, but he was the power behind them, leading forward every movement of the company,’ because its main business was building warehouses to handle the increasingly large quantities of sugar and molasses his ships were delivering to the port of Boston. It was a shrewd and effective step toward vertical integration: the sugar merchant ‘became the largest customer of the corporation,’ and ‘his interest in the plans for these stores, which gave promise of such profit to the company and such convenience to himself, was continued for a series of years, and he became personally familiar with every foot of ground about them.’

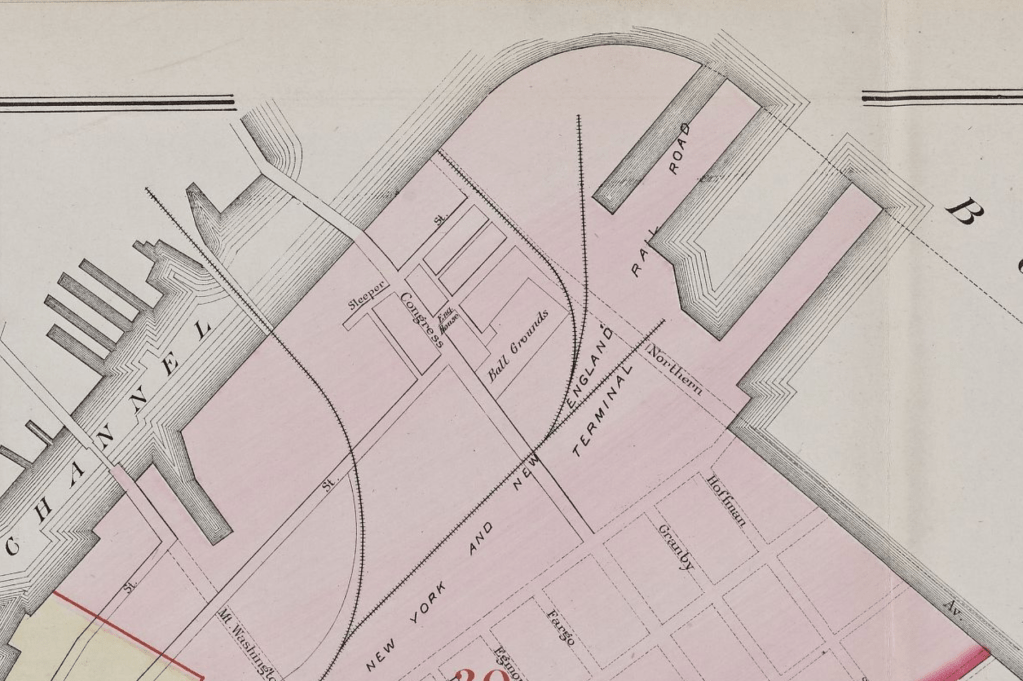

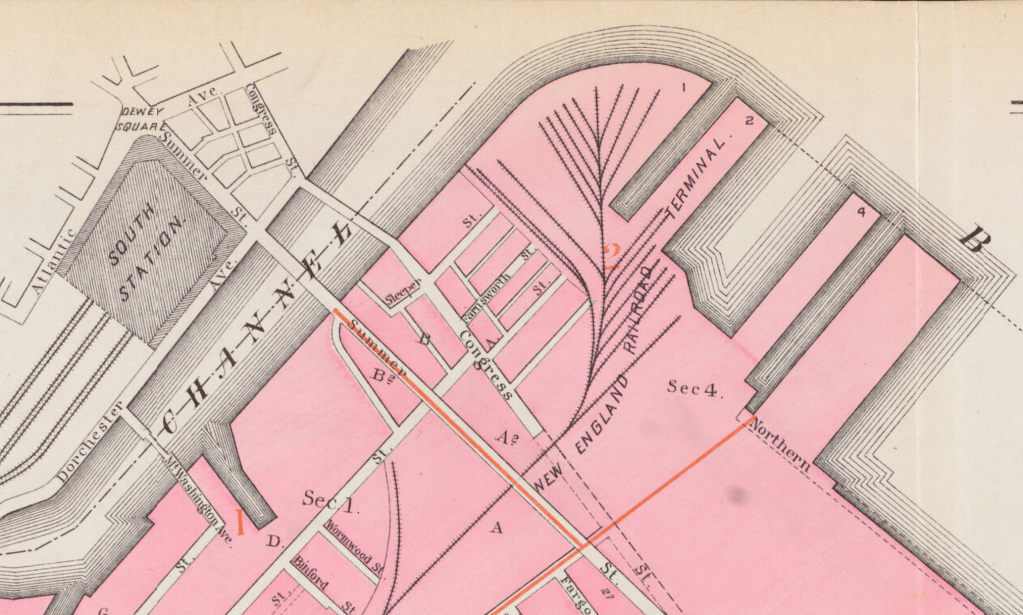

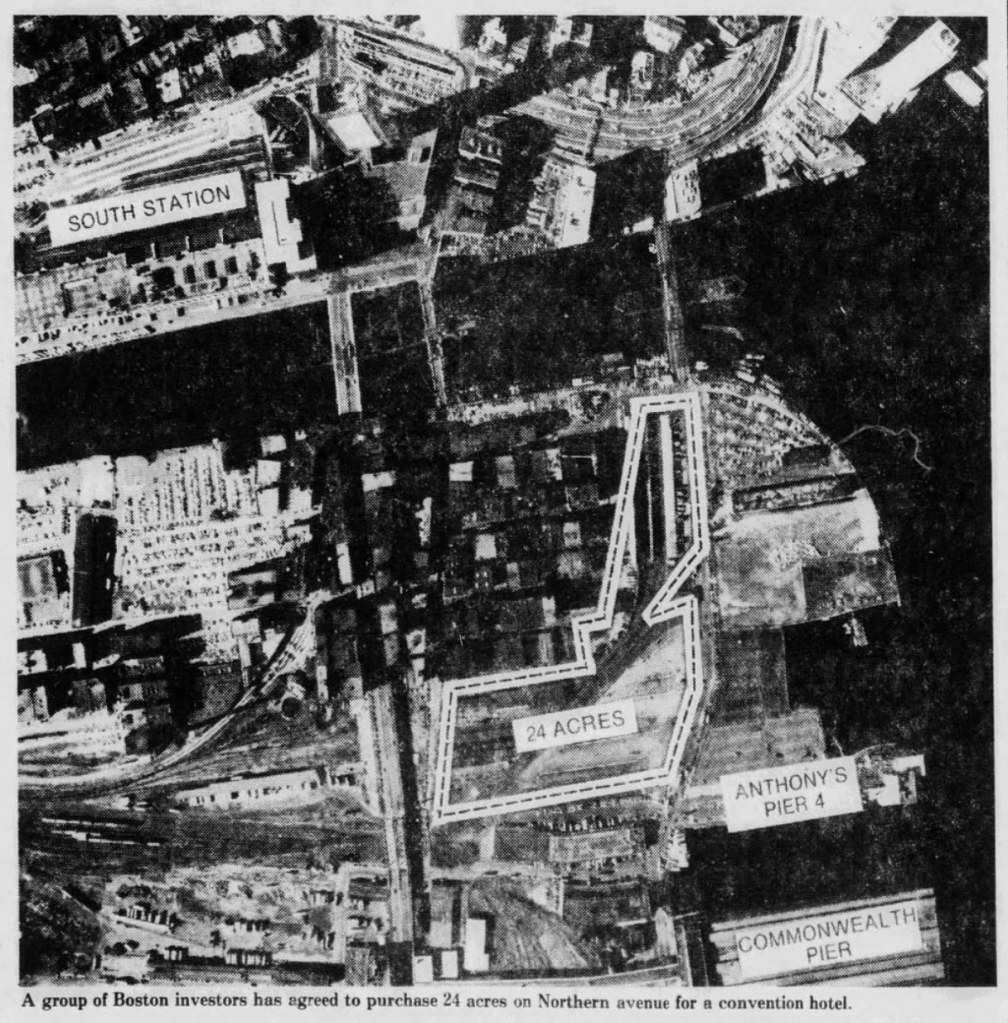

The Wharf Company made halting progress in filling the South Boston Flats until winning key approvals from the Legislature in the early 1850s; in an 1852 appeal to lift restrictions on their development rights, officials portrayed the firm as an underdog fighting a ‘class of opponents who represent the wealthy wharf owners of Boston. . . who are desirous of keeping up those very high prices of wharfage which are so injurious to the commerce of the State, and who fear the effect of competition with our wharf.’ Surveys from the period show the wharf jutting out from First Street along the upper edge of South Boston, largely unchanged between 1846 and 1852, but by 1868 it had extended far into the Fort Point Channel, about to present-day Congress Street. Most of the land was occupied by several vast molasses warehouses and a sugar refinery.

Over these decades Elisha Atkins was building a substantial fortune, his family’s rise in status indicated by their increasingly upscale choices in real estate: they moved to the then-fashionable Pemberton Square in 1856, bought a summer estate in Belmont in 1864, and in 1872 relocated again to a house on Commonwealth Avenue in the Back Bay, a neighborhood newly created on filled land much like that of the Wharf Company in South Boston. Edwin F. Atkins was born in 1850, and instead of going to college was trained to take over the family business, making his first visit to Cuba with his father at age 16. The young Atkins began working in the firm’s Boston office in 1868—in his memoir he recalls one of his duties was ‘to go through the cargoes of molasses to note the color and to taste hundreds of hogsheads to ascertain the quality’—and the following year was sent to Cuba to learn Spanish and pick up the local knowledge needed to run the trade in earnest. Elisha had shifted his attention to his duties as a director of the Union Pacific Railroad, a position that would result in his testifying before Congress as a bit player in the infamous Credit Mobilier scandal. Though Atkins himself wasn’t implicated in any crimes, the revelation of the fraudulent manipulation of railroad construction contracts became the signal case of corruption at the highest levels of finance and government during the Gilded Age.

Meanwhile, Edwin Atkins had begun his career in Cuba at a time of bloody upheaval. ‘Dear Father and Mother,’ he began a letter home in 1869, ‘I have arrived safely at this city without being captured by any rebels. . .’ The Ten Years’ War erupted on the island in 1868 when the sugar planter Carlos Manuel de Céspedes freed his slaves and launched an uprising ‘to throw off the Spanish yoke, and to establish a free and independent nation’; though ultimately unsuccessful in this aim, the rebellion and brutal decade of fighting, which resulted in as many as 200,000 deaths, would reshape Cuban society and its slave-based plantation economy in particular. On the eastern side of the island, César J. Ayala writes in American Sugar Kingdom, the war ’caused the destruction of many plantations and the liberation and migration of many slaves,’ such that it ‘had de facto done away with slavery, whereas in the western parts of Cuba slavery continued until final abolition in 1886.’ In his memoir Edwin Atkins recounted that, ‘The devastation of war, extravagant management, and the loss of slave labor led to the impoverishment and transfer of ownership of many of the Cuban sugar estates.’

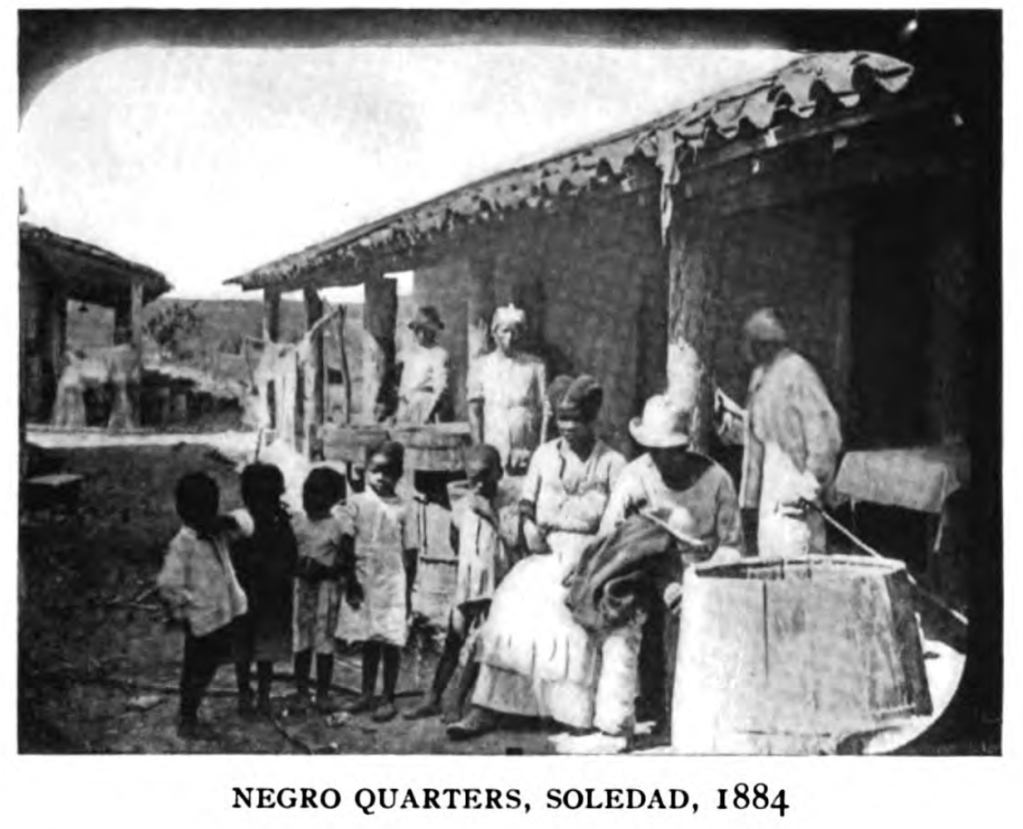

The years following the war marked the transformation of the Atkins merchant business into a vertically integrated sugar-producing concern. A profitable side of their operations had involved advancing credit to planters, many of whom were left destitute by the end of the fighting; according to historian Christopher Harris, the ‘family’s risk grew as more and more planters defaulted on their loans,’ and ‘as land prices collapsed after 1878, Atkins & Company was, in effect, forced into becoming a sugar grower.’ Similarly, around the same time the family acquired the Bay State Sugar Refinery, on Eastern Avenue in the North End, as the large buyer of Atkins product had become insolvent and unable to pay its debts to the firm. In the most momentous transaction, after years of foreclosure proceedings Edwin Atkins officially assumed ownership of the Soledad sugar plantation at Cienfuegos, on Cuba’s southern coast, in 1884. The question of whether and to what extent this acquisition made the Atkinses slaveholders has in recent years attracted renewed attention from institutions that have benefited from the family’s largesse.

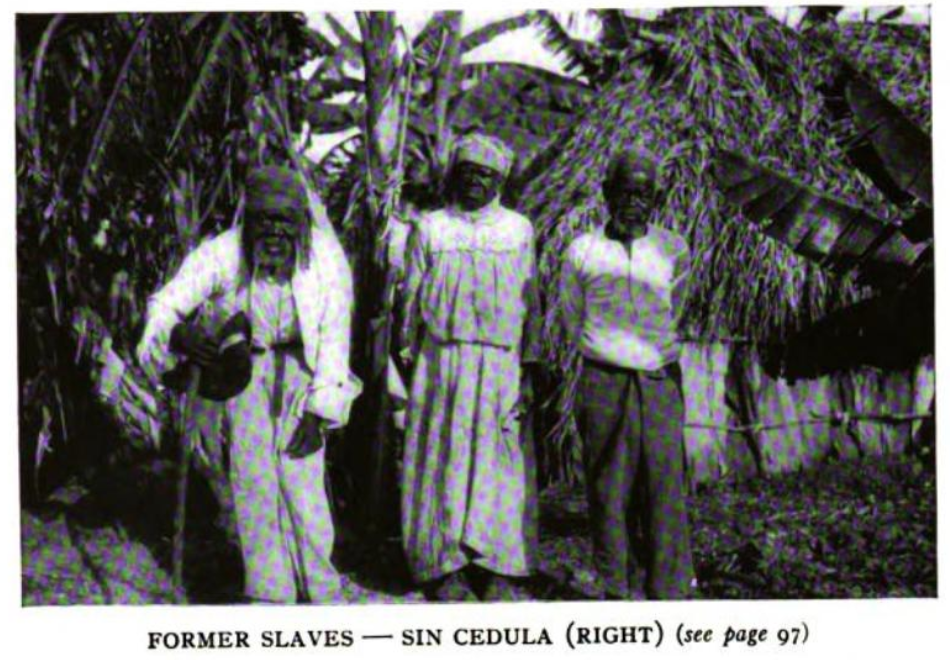

In 1880, as a result of the Ten Years’ War and a subsequent, smaller conflict known as the Guerra Chiquita, Spain enacted a law formally abolishing slavery in Cuba, though not immediately. The act ‘bound former slaves as patrocinados, or apprentices, to their masters for eight more years,’ notes legal historian Rebecca Scott, and ‘the cloak of patronato (patronage) covered a system that appeared to offer freedom but enabled masters to extract several more years of largely unpaid labor from their slaves.’ Citing Scott’s research, in 2022 the Report of the Presidential Committee on Harvard & the Legacy of Slavery included Edwin Atkins as a prominent example of the university’s ‘extensive financial ties to slavery’: ‘This [patronato] system was, in effect, slavery by another name. In fact, before Atkins purchased Soledad, the plantation’s owners sent a bill of sale to his business partners that listed 177 patrocinados as slaves, despite their new legal status. When E. Atkins & Company officially acquired the plantation, it came with at least 95 formerly enslaved patrocinados.’ In 1899 Atkins began financing the work of Harvard botanists to improve the yield of his cane crop, and an estate on the Soledad plantation became the Harvard Botanical Station for Tropical Research and Sugar Cane Investigation, later operated by the university as the Atkins Institution of the Arnold Arboretum for decades until its seizure by the Cuban government in 1961.

The Atkins memoirs and biographies don’t acknowledge or speak to their status as slaveholders one way or the other, but there are telling passages. In an account included in Helen Atkins Claflin’s family chronicle, Edwin’s wife Katharine records a visit from Sam Eliot, the son of Harvard President Charles Eliot, writing, ‘One of our old slaves came in one day while Mr. Eliot was there, and looking at him admiringly, said to me, “Niña, is that God himself?” He certainly was a very good looking young man and I suppose that may have been the old negro’s idea of the Lord.’ In his reminiscence of the era, recalling the ceremony that accompanied he and his wife’s arrival to Soledad each winter in the 1880s, Edwin wrote, ‘As the procession filed in front of us, many of the older African negroes would kneel and kiss our hands and feet, asking our blessing. These negroes addressed us as father and mother, and always called me master. They really considered themselves as our children.’ Decades after the Civil War had put an end to slavery in their own country, the Atkinses could live as old-fashioned plantation masters in their adopted home of Cuba.

In Boston, Edwin Atkins had joined his father as a director of the Wharf Company by 1884, and that year became involved in a boardroom battle over its management and future direction. In June the Boston Globe reported that a group of stockholders were complaining about the firm’s flagging financial position—one ‘claimed that thousands of dollars’ worth of business had been lost to the company, and the stock which should bring $57 per share had lately been sold for $25’—and had begun ‘inquiring into the company’s system of business, with the view of either putting a part of its land on the market for sale, or of leasing it at a rental for building purposes.’ Several factors apparently contributed to the decline of the Wharf Co.’s storage business: the disruptions to and restructuring of the Cuban sugar market, the ongoing consolidation of the domestic refining industry, and according to company director J.B. Russell in an 1887 letter to the Globe, ‘the unequal, improper and dishonest execution of the same custom laws and regulations in the different ports.’ That is, Boston merchants believed the examiner of the New York customs office in particular to be appraising sugar at a lower value of purity, and therefore a lower rate of duty for importers; the accusation was ultimately proven and the examiner fired. In his letter Russell claimed that receipts from sugar and molasses storage at the Boston Wharf Company’s warehouses totaled $74,000 in 1885 but ‘this year. . . will probably not exceed $20,000, and another year in all likelihood, will see the property devoted to other uses, its legitimate use practically destroyed by dishonesty.’

The company’s decline spurred the group of aggrieved shareholders to accuse the board of serious conflicts of interest: ‘The trouble seems to have originated in part in the election as directors of two or three stockholders who were at the same time among the largest customers of the company,’ the Globe reported, and ‘it had been insinuated by certain stockholders that these directors were getting wharfage at special rates.’ The allegation was aimed squarely at the Atkinses, and Edwin fired back to likely devastating effect:

He said that at a previous meeting surprise had been expressed that the Messrs. Atkins did not resign as directors, inasmuch as they were the largest customers of the Boston Wharf Company. At that time, he said, the need no longer existed, as his firm had withdrawn their business and engaged storage room for some 7000 hogsheads of sugar among other wharves. As to the statement that his house obtained lower rates of the Boston Wharf Company than could be obtained at other wharves, he said that he placed before the committee receipted bills of nearly all the wharves doing a sugar business, all of which showed lower rates than those charged by his company. . . In conversation after the meeting Edwin F. Atkins said his firm handled 60,000 hogsheads of sugar annually, and had heretofore given all their business to the Boston Wharf Company. And in addition to this they had indirectly brought fully one-half of the company’s business to its wharves and bonded stores.’

Not only would he decline to resign as a director, Atkins had actually pulled his sugar out of the Wharf Company’s sheds anyway, and up to that point his family’s business had been the primary reason why the landmaking venture existed in the first place. Who exactly did these shareholders think they were dealing with?

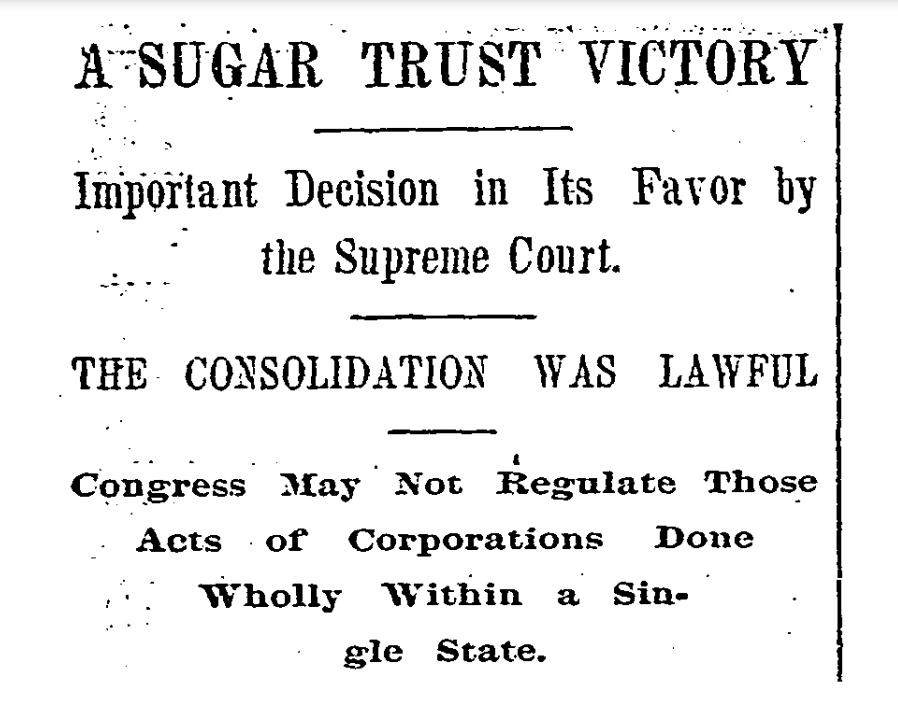

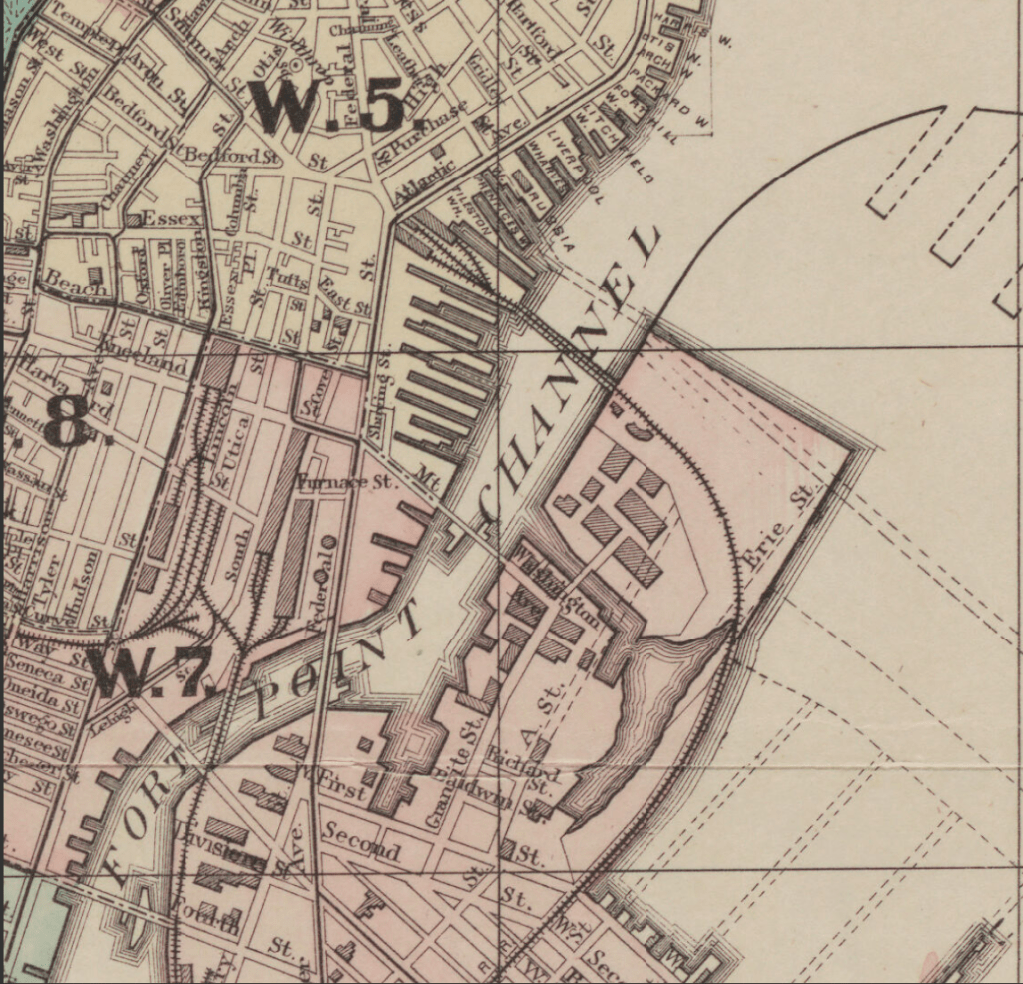

Edwin Atkins stayed on, and would serve as president of the Boston Wharf Company from 1896 until 1925, the period when it transitioned fully into an industrial real estate developer and created the Fort Point neighborhood as it largely still stands today. Though no longer the company’s central source of revenue, the business of sweetness remained a significant physical presence in the area—through the Chase & Co. confectionery, built on Congress Street in 1887; the Necco factory, completed in 1902 and enlarged with two additional buildings in 1907; and the expanding footprint and evolution of the Standard Sugar Refinery, which had operated at a location halfway up the channel, on the company’s earliest made land, since at least 1868. In 1887, Atkins agreed to merge the Bay State Sugar Refinery into Henry O. Havemeyer’s newly incorporated and soon-notorious Sugar Trust, which controlled the Standard Sugar Refinery; the news of the shutdown of the Bay State the following year was notable enough to make the front page of the New York Times, the headline just under the masthead reading, ‘Closed by the Trust.’

Atkins’s involvement in the Sugar Trust would, like his father, result in his testifying before Congress in 1911, where he acknowledged that the Bay State refinery was closed and its machinery removed to the Standard to concentrate Boston’s refining capacity, and that he had received stock in the Trust as part of the deal. (Atkins claimed the Bay State was a money-losing operation, and that, rather than a nefarious bid to stifle competition, the ‘purpose of the combination was to. . . turn the business of the weaker houses over to the best, and reduce the cost of refining. . . so that we could sell to the consumers of the country at a lower figure than we would otherwise be able to sell for.’) The Trust, which after the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 was reorganized as the American Sugar Refining Company, became a leading corporate villain of the era, embodying the most flagrant excesses of encroaching monopoly: ultimately controlling 98 percent of sugar refining in the United States, it ‘often operated on the edges of the law,’ Ulbe Bosma writes, ‘and it perpetrated major legal offences, ranging from illegal transport arrangements with the New York Central Railway Company to multiple cases of defrauding customs.’ The Trust made a crucial contribution to the era of corporate consolidation with its 1895 victory in the United States v. E. C. Knight Company case, in which the Supreme Court drastically curbed the ability of the federal government to enforce the provisions of the Sherman Antitrust Act.

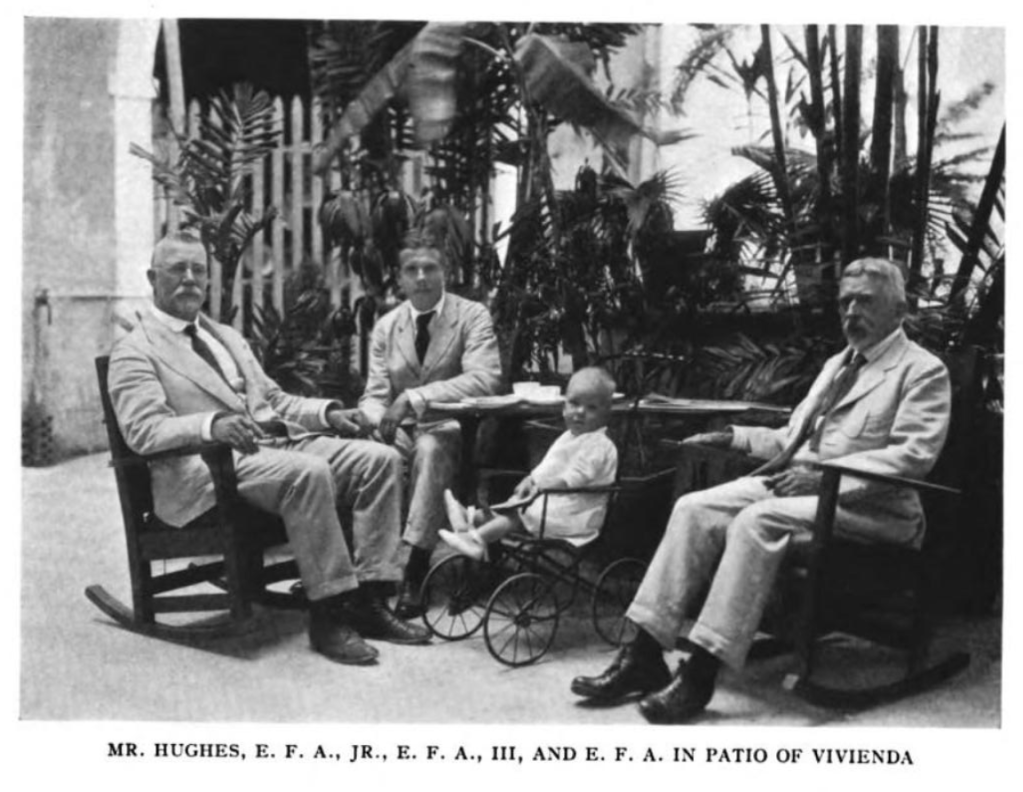

Following the death of Henry O. Havemeyer in 1907, Atkins took on a central role in overseeing the American Sugar Refining Co., serving variously as vice president, acting president, and chairman of the board of directors, such that for a period of time he was officially running the dominant refining concern, plantations in Cuba that controlled one-eighth of the island’s total sugar production, and the Boston Wharf Company, on whose land one of his refineries and the nation’s largest candy maker both operated. (There’s no record of Atkins himself having a direct interest in Necco, but it’s fair to infer that the company was a major customer of American Sugar Refining, given their proximity in Fort Point and the latter’s stranglehold on the industry; a 1952 Report of the Federal Trade Commission on Interlocking Directorates found the firms shared an ‘indirect interlock’ via respective company directors who served together on the board of the Boston Elevated Railway.) Altogether, Atkins presided over a fully integrated, continent-spanning empire of sugar.

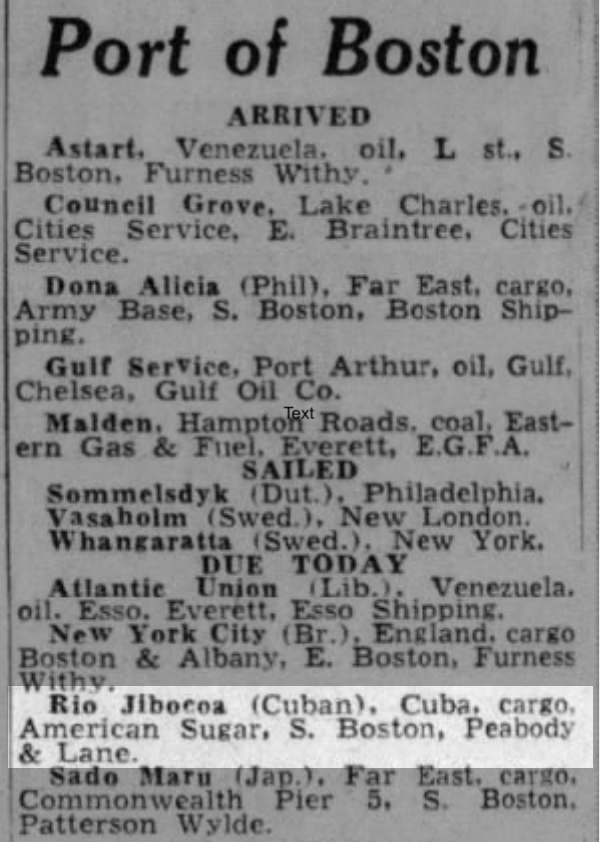

American Sugar Refining introduced the famous Domino line of packaged consumer products in 1900, and later built large, neon-lit signage advertising the brand over its refineries in Boston, Brooklyn, and Baltimore, where the sign has become an iconic visual element of the city’s Inner Harbor. The Domino Sugars sign in South Boston has long since come down, but we can see how it would have looked looming over the Fort Point Channel in the most striking photograph surviving from the area’s waning industrial era. Captured by engineer and entrepreneur Nick DeWolf, the image shows the Cuban cargo ship Rio Jibacoa docked next to the American Sugar refinery, the Domino Sugars logo glowing bright, with the Boston Wharf Company Industrial Real Estate sign and the chimney of the Necco factory appearing faintly in the far background, everything mirrored in the glassy stillness of the channel’s surface. A notice in the Globe recorded the vessel’s arrival on May, 4, 1960, a full year and a half since the final triumph of Fidel Castro’s revolution over the regime of Fulgencio Batista. The American Sugar Refinery relocated to Charlestown at the end of 1960, its channel-side site taken over by the Gillette razor company, and imports from Cuba were officially banned by President John F. Kennedy in February of 1962. The prior year, the new Cuban government confiscated the Atkins’s Soledad sugar plantation.

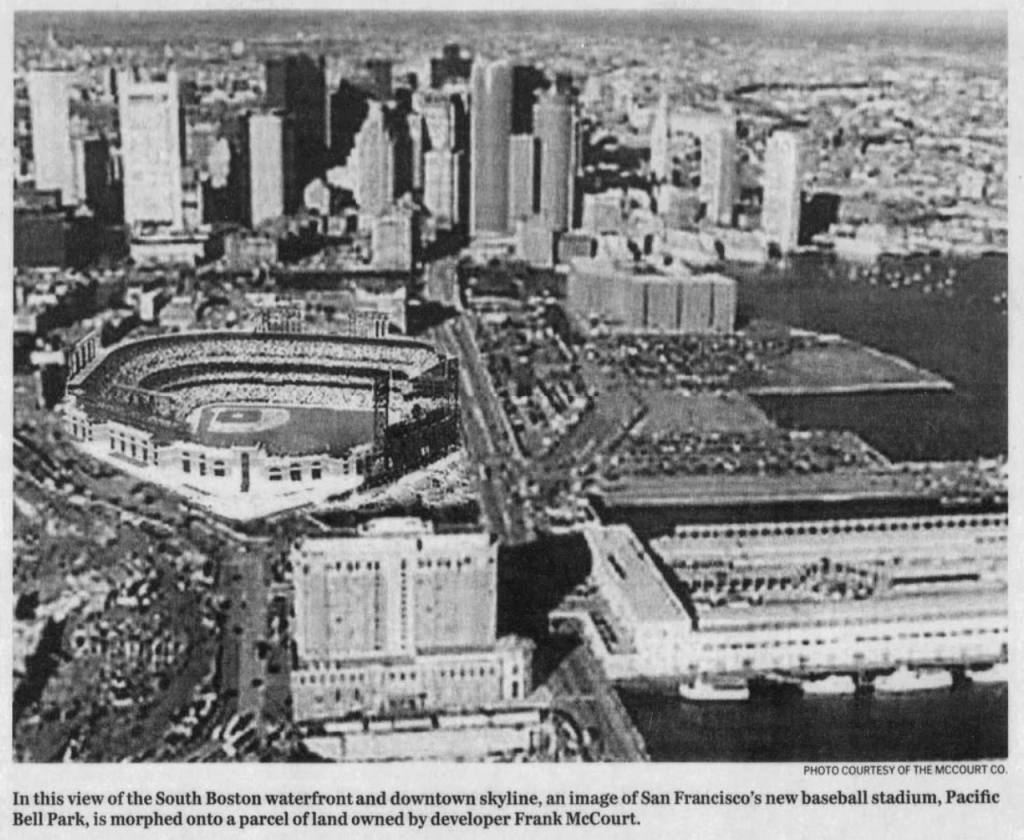

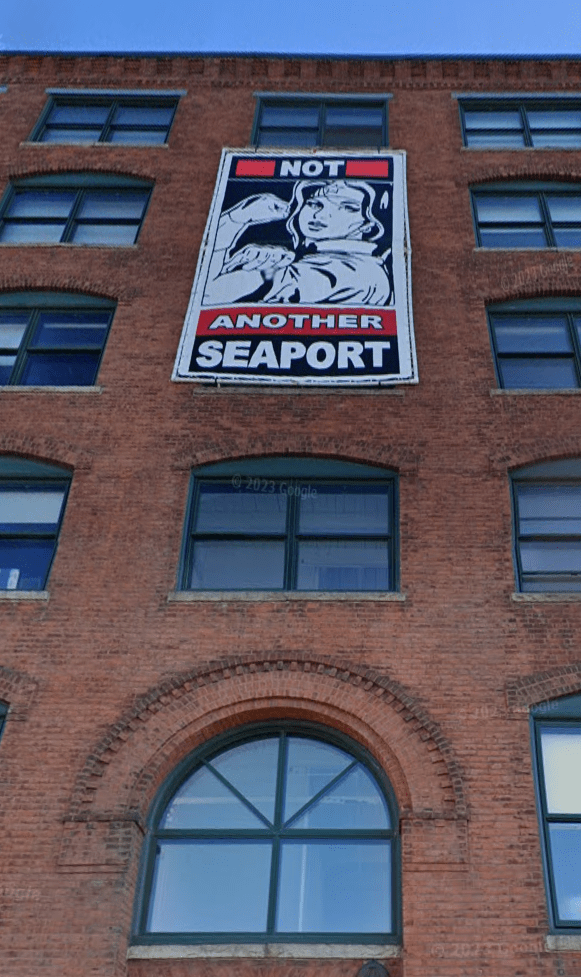

Walking along the Fort Point Channel today, it’s hard to imagine that huge oceangoing ships once traversed its waters, unloading cargos of raw sugar grown and milled in Cuba, to be further processed at a refinery that had operated at the same location for nearly a century. There are few lingering reminders of the long and complex history of sugar in the neighborhood. While there is a plaque mounted on a Summer Street building commemorating the ‘Center of the Boston Wool Trade,’ the legacy of the Atkins family and its stewardship of the Boston Wharf Company—a legacy bound up with the horrors of the Atlantic slave trade, the decades-long exploitation of workers enduring the punishing conditions of the cane fields, and the emergence of imperialistic industrial monopolies—is little noted, and not well remembered. The most visible remnants of the sugar business relate to the final link of the commodity chain, when the refined material was transformed into delightful treats for mass consumption: the Necco factory buildings, Necco Street, and Necco Court record the palatable side of a story that in its full telling can be harder to swallow.

In a 2000 Boston magazine article detailing a recent trip to Cuba by Atkins descendants—’a combination of family reunion and political fact-finding mission’—former Congressman Chet Atkins and his cousin Dr. Elisha Atkins reflected on the troubling origins of their patrimony. ‘Growing up in the ’60s, for people like Chet and me,’ Elisha said, ‘meant that coming from a family owning a sugar plantation in Cuba was nothing we really wanted to talk about or acknowledge.’ Regarding the legacy of his great-grandfather Edwin F. Atkins, Chet said, ‘The Boston Unitarian didn’t free his slaves until the last possible moment, because they were an asset on his books, and he wanted to be able to depreciate the asset. I think the whole thing is coming to grips with a crazy set of contradictions that he was a paragon of American imperialism, that he in fact developed and refined some of it, bought governments and elections, bent US policy and presidents to achieve his end, which was greater profitability for operations.’ But, he continued, ‘He was also an extraordinary philanthropist. . . I talked to children of the slaves, and they had enormously fond memories—I was really amazed to find—of Edwin Atkins, and particularly Katherine Atkins, good feelings.’ Family ties can color perceptions, and encourage us to think the best of relatives and ancestors. So too it is with nostalgia, perhaps of the kind evoked by a favorite candy from childhood: we tend to fixate on the sweeter memories, however bitter the reality may have been.