In December 2016, at a press conference announcing the release of the landmark Climate Ready Boston report, then-Mayor Marty Walsh declared a new approach to building in the city. Citing the recent rebranding of the Boston Redevelopment Authority to the Boston Planning & Development Agency, Walsh insisted the update was less a simple name change than a ‘whole cultural change.’ ‘It’s about truly planning an entire area and planning for the future,’ he said. ‘When you look at the waterfront today, if we could go back in time 30 years and start looking at the different buildings that were built… if we really thought it through, we could have done some real spectacular things during the development phase. We missed that opportunity, so now we have to figure out how do we do it and then with the new development coming in, have the new development prepare for the future.’

Two days later, the Boston Herald ran an article interviewing developer John B. Hynes, III, the main player in the planning of the 23-acre waterfront megaproject dubbed Seaport Square. ‘I have my doubts,’ Hynes said of the city’s climate projections. ‘The global warming phenomenon that everybody’s worried about is nothing more than historic cycling.’ The Mayor’s report identified the South Boston Waterfront as the area at the highest risk of damages due to sea level rise and chronic flooding, but one of its most prominent builders wasn’t as concerned. ‘If these guys are all right, I guess the next generation will be developing out in the Berkshires. Eastern Massachusetts will be under water, which is crazy,’ Hynes said. ‘I’m not going to get into the science of it because there’s too much science.’

By then, Hynes’s firm Boston Global Investors and majority partner Morgan Stanley had already completed an impressive ‘exit’ from the Seaport Square project, netting north of $360 million in profit in less than ten years. Following the initial $204 million acquisition of the land from Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp in 2006, Hynes estimated a further $80 million went into the permitting process and infrastructure work, and once the required approvals were secured, the Seaport Square blocks were sold in a series of deals totaling $665 million. A triumphant Hynes put on an elaborate show for the 2014 groundbreaking of the centerpiece One Seaport Square complex, which featured live models posing in stage-set creations of a luxury condo living room and rooftop, a movie theater, and an Equinox gym. Following remarks in which he lauded the Seaport District as representing ‘the future of our economy,’ former construction worker and union head Mayor Walsh hopped in the cab of an excavator for the big shovels-in-dirt photo op.

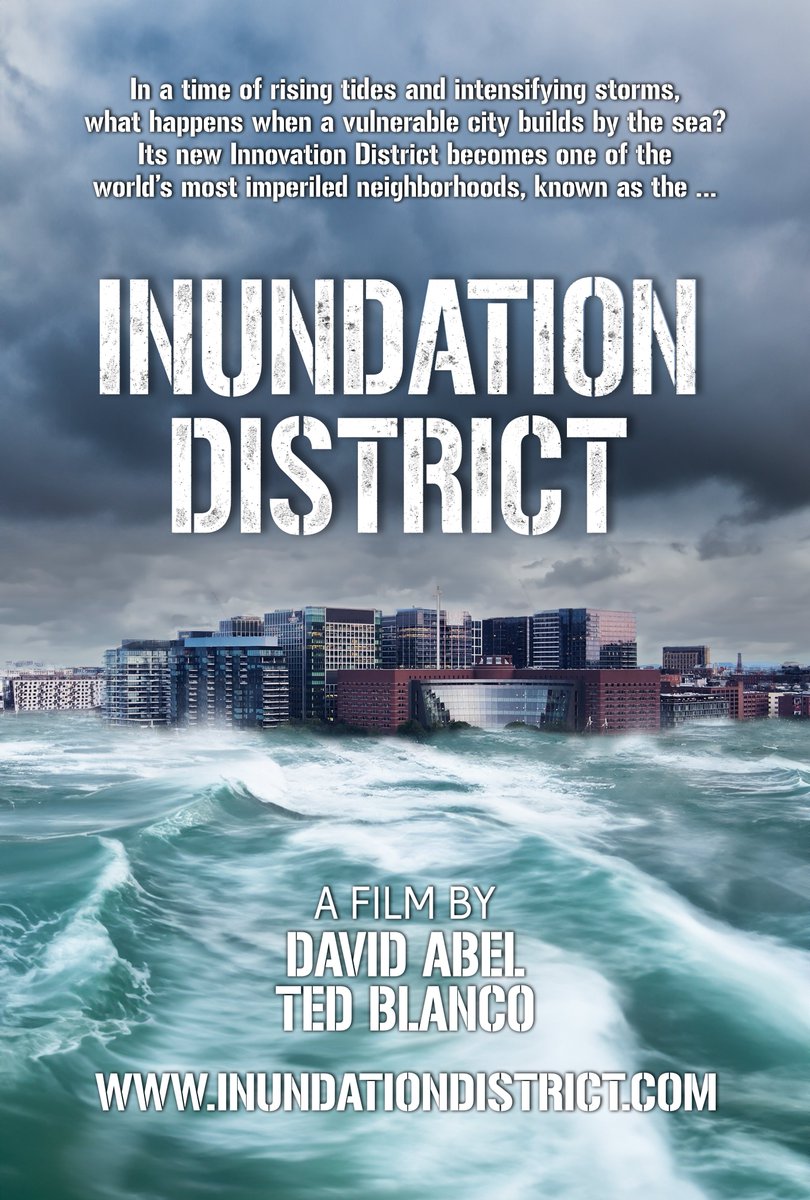

The premise of David Abel and Ted Blanco’s new documentary Inundation District is that such spectacles amounted to shortsighted hubris at best, and willful negligence at worst. How, the film asks, could the city of Boston embark on a multibillion dollar buildout of a brand new neighborhood on filled tidal flats when the threat of sea level rise and worsening coastal storms was already widely understood? And what is to be done about it now?

These questions have become stock media and conversation fodder in Boston, but Inundation District offers the most compelling and accessible rendering of the subject yet. It deserves wider distribution, and an audience well beyond just the Bay State. Timely, informative, and engrossing, the film weaves history lessons and technical expositions with more cinematic moments played up for pathos or outrage, and Abel covers a lot of ground over a 79-minute runtime. If anything, possibly too much: in its attempt to explore all the angles, and make the most of a large, well-selected cast of characters, Inundation District can feel stretched a bit thin. But that is partly the nature of what is a vast and complex set of issues to consider, and the documentary still succeeds as both a hyper-local investigation and a cautionary tale on a more universal level.

Will it persuade the doubters and deniers? Probably not, and if that’s not quite the film’s remit, there might be some truth to the inevitable charge of preaching to the choir: so far it has only been shown at select events and venues, some in partnership with local environmentalist groups, in places like Cambridge and Nantucket, where likely most in attendance arrive well-primed to lament the insane overbuilding of the Seaport. In one ‘meta moment‘ at a recent screening at Boston University, some of the same Extinction Rebellion activists seen in Inundation District interrupted the Q&A to grill and make demands of Massachusetts Climate Chief Melissa Hoffer—though the organization later clarified its ‘appreciation and admiration to the creators’ of the film.

Many others are not so alarmed, or at least view other issues as more pressing. A 2022 poll from MassINC sponsored by cable billionaire Amos Hostetter’s Barr Foundation—which also provided support for Inundation District and the 2016 Climate Ready Boston report—found that while 77% of respondents said climate change posed a ‘very serious’ or ‘somewhat serious’ problem for Massachusetts, only 47% ranked it as a ‘high priority’ for the state government to address, compared to 68% who said the same regarding ‘jobs and the economy.’ This is roughly in line with recent nationwide figures: in a 2023 Pew Research Center survey, 37% of Americans said the federal government should prioritize ‘dealing with global climate change,’ well below support for ‘strengthening the nation’s economy’ at 75%.

There may be doubts about the reliability of public opinion polling, but such results point to an intuitively understood dilemma at the heart of debates surrounding efforts to mitigate climate change. That is, the idea that even if we accept the looming danger of the situation, we can’t afford to do anything too sudden or drastic about it. As one interviewee in the Pew survey said regarding the transition to using renewable energy sources, ‘I’m fine with the change. What I’m not fine with are the demands and the urgency to change, which then has a major impact on the economy.’

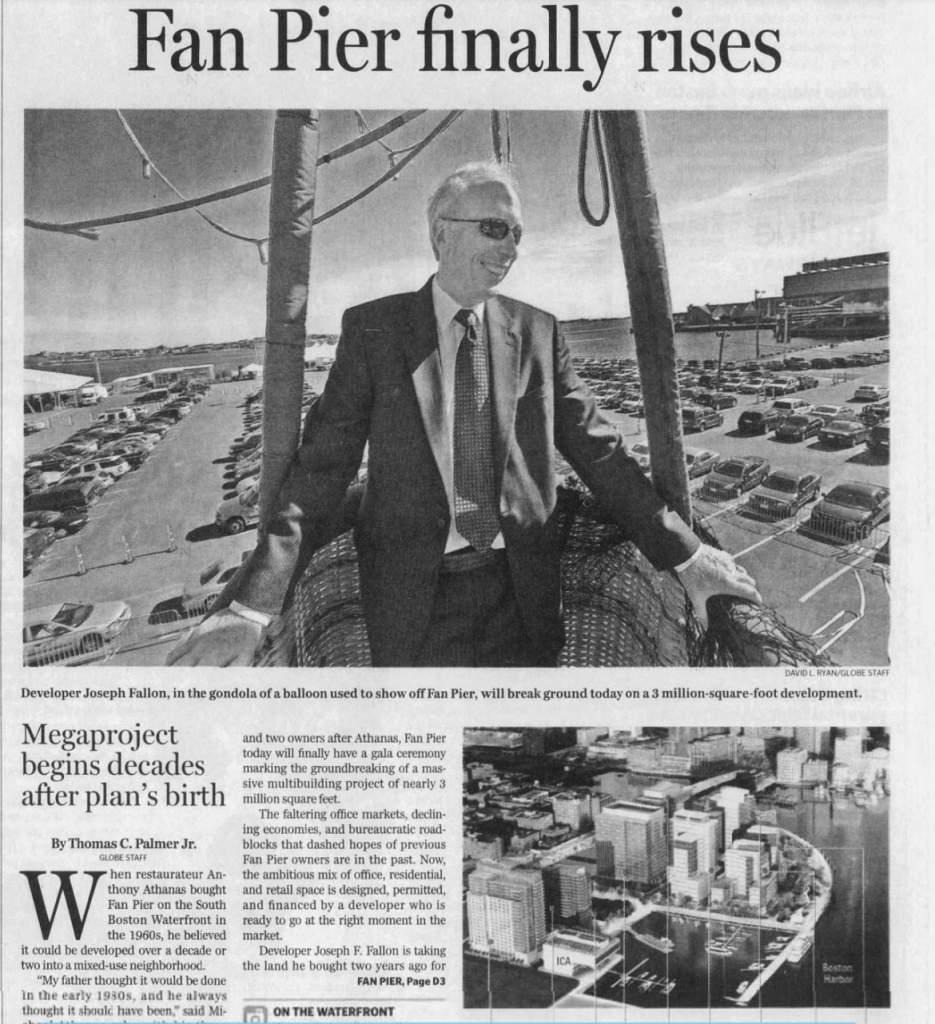

The parallel with the rise of Boston’s gleaming, seaside ‘Innovation District’ is clear enough. There was, and is, simply far too much money at stake not to build. The most coveted land at Fan Pier and Seaport Square had been tied up in litigation and planning battles for decades, so that when it at last came time for construction to begin, the mood was jubilant. ‘Remember all the fights we had on this one?’ Mayor Thomas Menino said ahead of the groundbreaking ceremony for Joseph Fallon’s Fan Pier development in 2007. ‘The day finally has come to see Fan Pier rise out of the ground to become a very important part of the city’s economy.’ The sense of long-awaited momentum on the waterfront provided a rare source of hope when the global financial crisis and recession hit soon after; a 2010 Globe report on the BRA’s pending approval of Hynes’s Seaport Square anticipated that the project’s initiation ‘could signal a reawakening for private development, which has been largely dormant in the city since credit markets froze.’

Over the next decade the Seaport would lead and come to symbolize the broader post-recession building boom in Boston. The BPDA’s 2018 Economy Report identified 124 developments under construction across the city at a total value of $11 billion, with $1.9 billion of that rising in the South Boston Waterfront, the highest of any neighborhood. According to Boston Global Investors, Seaport Square’s projects have to date ‘created approximately 10,000 construction jobs [and] 20,000 permanent jobs,’ with the rise in property values ‘resulting in increased real estate tax payments to the City of Boston of approximately $45 million annually.’ As Mayor Walsh said at Hynes’s grand groundbreaking for One Seaport Square, ‘We are seeing our city’s economy work right here in front of us.’ Boston might pride itself on world-renowned tech and life sciences sectors, but builders still largely call the shots: Suffolk Construction’s John Fish has ranked near or at the top of every Boston magazine Power List since 2012, and Walsh’s 2013 election victory was widely attributed to his rock-solid backing from the building trades unions.

Inundation District doesn’t deal with all the tricky implications at play in the world of Boston power politics and the real estate game—to pull those threads would probably result in a separate film entirely—but it does prominently feature one developer as a stand-in for the rest. This is, of course, WS Development, the company that has more than any other defined the look and feel of the central Seaport area, initially partnering with John Hynes and Morgan Stanley in 2007 and later acquiring the remaining unsold 12.5 acres of their land for $359 million in 2015. In a scene played for irony, the filmmakers crash WS’s festive 2021 ribbon-cutting for ‘The Rocks at Harbor Way’ and speak to executives Amy Prange and Yanni Tsipis, and to his credit Tsipis agrees to a longer interview, according to Abel the only developer willing to do so. Tsipis emphasizes the firm’s long-term interest in the area, and gamely walks through various flooding resilience measures they’ve implemented—building at a raised grade, putting mechanical systems on a higher floor, designing a parking garage to double as a vast stormwater repository—but is ultimately set up to take the fall in the film’s climactic moment.

The scene has Abel, otherwise unheard and unseen, at his most confrontational, and serves its purpose to heighten the drama, but at the risk of washing out some nuance. WS deserves plenty of scrutiny for its choices in the Seaport, from specific instances of abandoning or altering promised public spaces to an overall paucity of vision, in thrall to brand names and moneyed tenants, but Tsipis is indeed one of the more ‘enlightened developers,’ as Abel told Boston Public Radio, and there doesn’t appear to be reason to doubt the firm’s claim that they ‘plan to own the area for a very long time.’ The Seaport’s most egregious practitioner of climate denial and windfall land-flipping doesn’t feature in the film, nor do any other major waterfront operators, like the Fallon Company, Fidelity Investments, or the federal government. Which is all to say the situation is complicated, bigger than one developer or landowner, and demanding a fully integrated preparation and mitigation strategy that has yet to be realized. As Deanna Moran of the influential Conservation Law Foundation advocacy group has said, ‘This ad hoc, parcel-by-parcel, project-by-project resilience approach is not a long-term solution.’

Where do we go from here? The film looks at a few proposals to stave off the worst, all either conceptual, expensive, or somewhat outlandish: a massive seawall along the outer mouth of the harbor, a deployable storm surge barrier that could turn the Fort Point Channel into a huge drainage basin, an Emerald Tutu of ‘floating biomass modules’ to diminish high wave energy. On the development side, the Coastal Flood Resilience Overlay District guidelines were added to Boston’s zoning code in 2021, and this past December the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection issued new draft wetlands regulations that have already drawn criticism from the business community. ‘Yes, we all deserve to be protected against climate change flooding,’ a recent Banker & Tradesman editorial grants. ‘But every state and local agency that touches the built environment must keep maximizing housing production top of mind at all times. After all, what use are legal and regulatory protections to someone who can only afford to sleep in their car under a bridge?’

As it happens, Inundation District does spotlight a man, Nathan Wyatt, who sleeps under a bridge in the Seaport, the Harborwalk underpass near the waterside Barking Crab restaurant. His message is the opposite: all this building is for naught, certainly not intended to help people like him in the first place, and anyone who can’t see what’s coming is hopelessly deluded. Taken by surprise on a high tide flooding day, he wakes up to find blankets and belongings soaked through, and eventually leaves the area to seek drier shelter elsewhere.

So we can’t afford to do too much, and we can’t afford not to. However the broader climate battles play out in Boston and across the country, one thing is certain: development in the Seaport is not stopping anytime soon. ‘This place is going to be subject to devastation,’ former Mass Audubon and Coastal Zone Management official Jack Clarke says indignantly in the film, ‘and the building continues.’ Directly on the harbor’s edge, the St. Regis condo building opened in late 2022, Fidelity has commissioned a large-scale renovation of its Commonwealth Pier office and retail complex, and the last piece of Fallon’s Fan Pier is set to rise on Parcel H diagonal to the Institute of Contemporary Art. Along the flood-prone Fort Point Channel, Eli Lilly will soon move into its new $700 million Institute for Genetic Medicine, Related Beal has planned the $1.2 billion mixed-use Channelside project, and Gillette is now making moves to undertake a major redevelopment of its longtime 31-acre manufacturing campus.

They say that we have to keep building here, that ‘there’s too much science,’ and that attempting anything truly ambitious in the way of adaptation or resilience just won’t pencil out. More than a failure of imagination, this mindset speaks to a dire lack of ‘civic solidarity,’ as the novelist Greg Jackson has put it. ‘Regardless of how one estimates the financial burden of massive refugee flows, failing cropland, lost coastline, disease, and crippling storms,’ he writes, ‘the cost of taking mitigating steps today pales in comparison. The current price of insurance, in other words, is cheap. The problem is that no person, company, or nation can take out a policy on its own. We have to go in on it together or it won’t work.’

The Seaport is not the only neighborhood in Boston at risk, and Boston is just one of many cities situated perilously low and close to the ocean. In Inundation District multiple people invoke the idea that water seeks its own level, that despite what we might or might not do, we will always be at the mercy of unyielding and dispassionate laws of nature. Spilling over walls or flowing through cracks, the flood will come rushing in, and we will have prepared ourselves and our homes or not. Sooner or later, water finds a way. Will we?

I’m happy to say I finally got housing.

LikeLike

That’s great to hear, Nathan, thanks for the update and best wishes

LikeLike