Why the City of Boston can’t fill a deep pothole in the middle of a busy commercial strip

We seldom think of streets as private spaces. The word itself connotes openness, freedom, the opportunity and danger of the public realm, and has for many centuries: the OED notes the Old English stræte could mean ‘the public square or forum of a town or city,’ and modern usage still closely links all manner of commerce, politics, and culture to the street. Main Street, Wall Street, streetwalker, street fight, street food, streetwear, street cred. ‘To take to the streets’ is ‘to assemble in a public place in order to engage in a political revolt or protest.’

Thomson Place in the Fort Point neighborhood of Boston is a street by any definition, and indeed has become something of the main drag of the surrounding area, home to the Trillium brewery, Trader Joe’s grocery store, four restaurants and counting, a medical clinic, and several corporate offices. There is a Marriott hotel at one end, and a Shake Shack and Silver Line transit station at the other. Its calm, one-way traffic is a refreshing respite from the rushing clamor of both Seaport Boulevard and Congress Street, and its historic, human-scaled architecture stands in stark contrast to the hulking new towers of the master-planned Seaport Square project nearby. But Thomson Place is technically not a public space. It is a ‘private way,’ not owned by the city of Boston, but by Invesco Real Estate and Newton-based Crosspoint Associates.

How did a global investment management company and regional real estate firm come to own this old street and the early 20th-century warehouse buildings lining it? It’s a bit difficult for the layman flâneur to untangle, such are the convoluted workings of urban development and the decaying state of the public internet and search engines, but we can start with the invaluable Fort Point Channel Landmark District

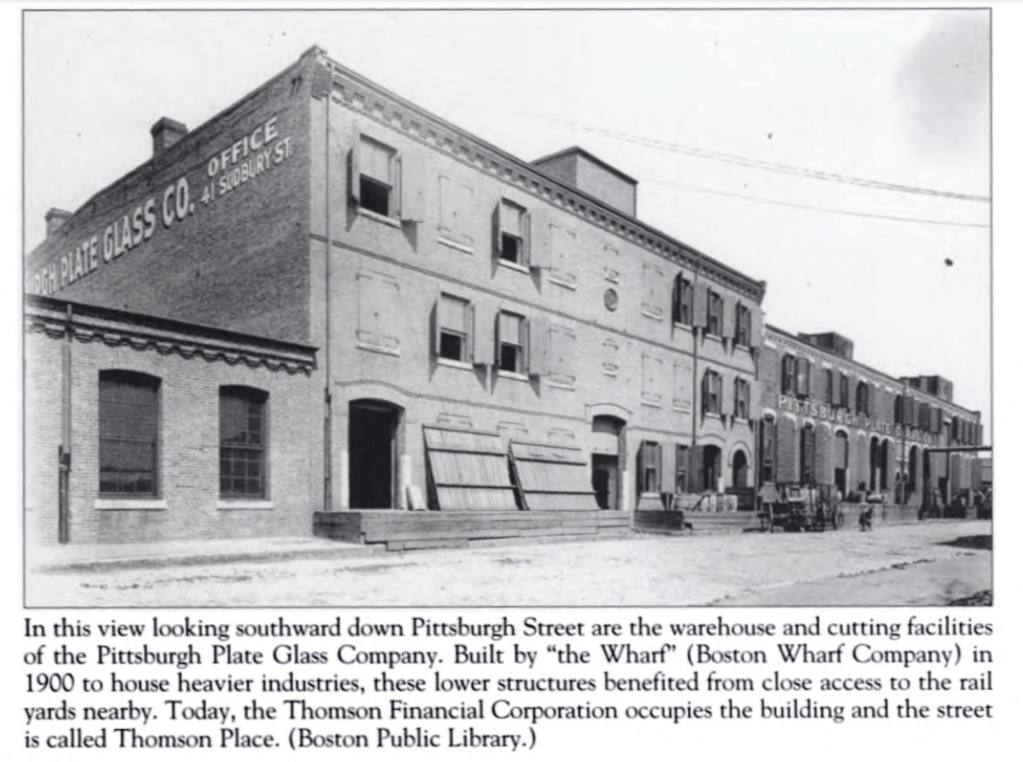

Study Report. The story goes something like this: the Boston Wharf Company, which built more or less the entire Fort Point district from scratch starting in the mid-nineteenth century, laid out the A Street Extension in 1896, which was later named Pittsburgh Street for the Pittsburgh Plate Glass Company that occupied a cluster of buildings at the northern end of the street, including the striking, low-slung warehouse that now hosts Trader Joe’s.

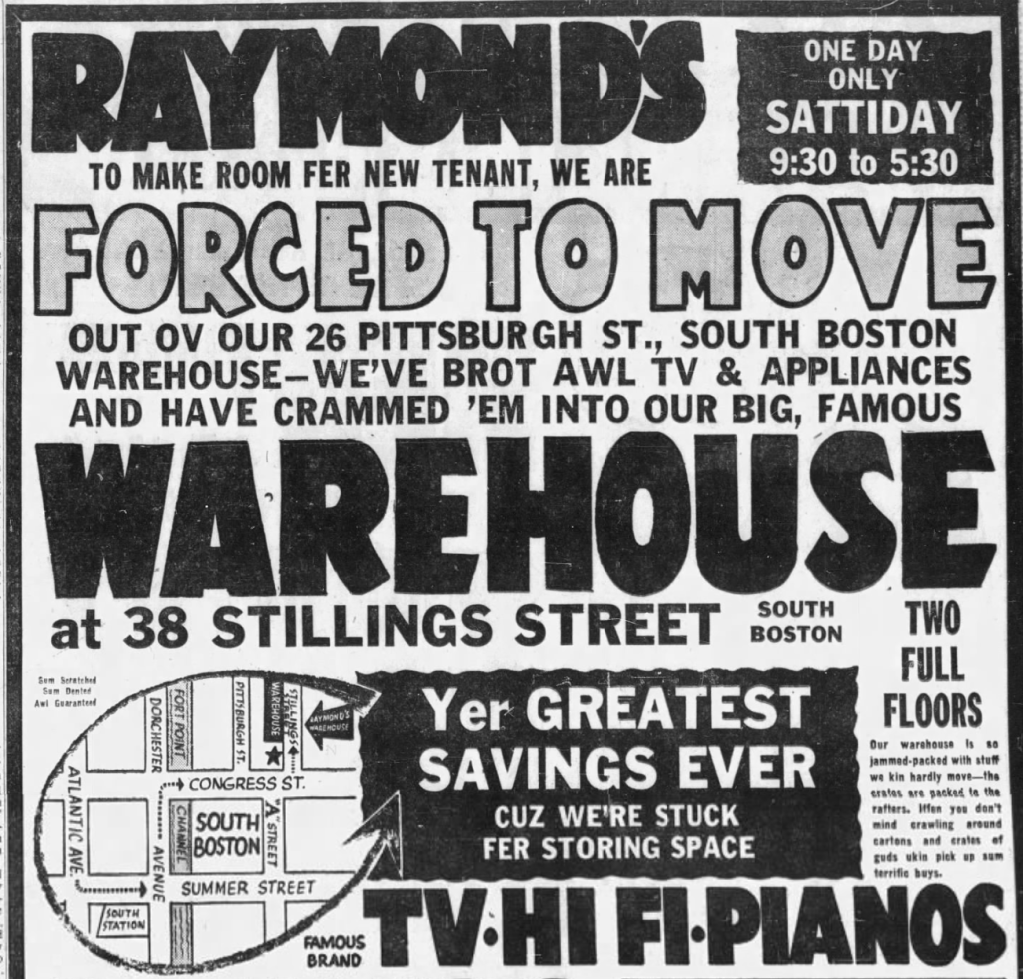

From there it gets hazier, requiring a deep dive into the Globe archives for clues as to what was going on during the ‘dark’ decades between Fort Point’s industrial heyday and its ongoing revitalization from roughly the 1980s onward. In 1954 there’s a record of the Central Wool Warehouse Corporation occupying the building at 26 Pittsburgh Street, which then served briefly as some kind of home appliance clearing house for the once-prominent department store Raymond’s, a more downmarket competitor to Filene’s and Jordan Marsh. Its advertising copy employed an eccentric, ‘swamp Yankee’ vernacular full of creative misspellings:

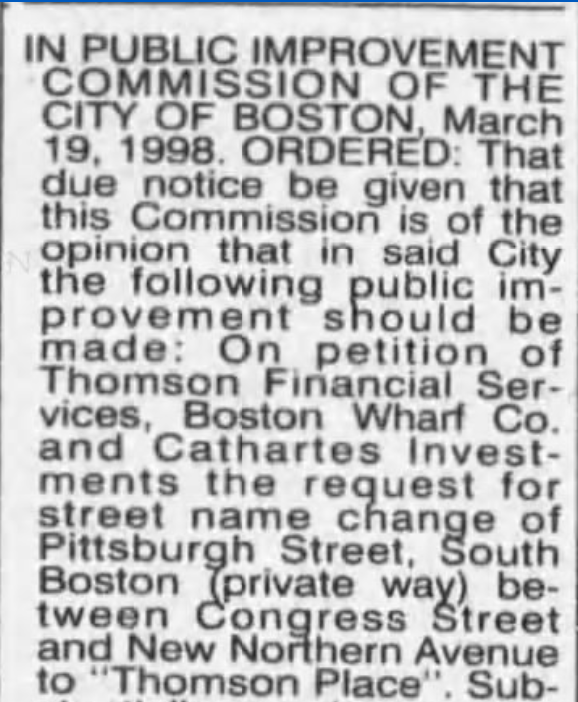

26 Thomson Place now houses the Amazon-owned One Medical primary care clinic. The renaming from Pittsburgh Street dates to 1998, at the request of the Boston Wharf Co. and its flagship tenant Thomson Financial Group, which began occupying Fort Point office space as early as 1982, launching a trend of major corporate moves to the South Boston Waterfront decades before the likes of Vertex Pharmaceuticals followed suit.

A December 2003 Globe article has the details:

When Thomson, then known as Boston Business Research, first moved its employees into 10,728 square feet of space at 12 Farnsworth St. in 1982, many adjacent buildings were empty. Daniel Pleines, vice president for real estate at Thomson, said the vacancies allowed the company to grow incrementally but steadily. In 1985, the company took its first entire Boston Wharf building.

The amount of Thomson’s Boston Wharf space peaked at almost 500,000 square feet in 2000.

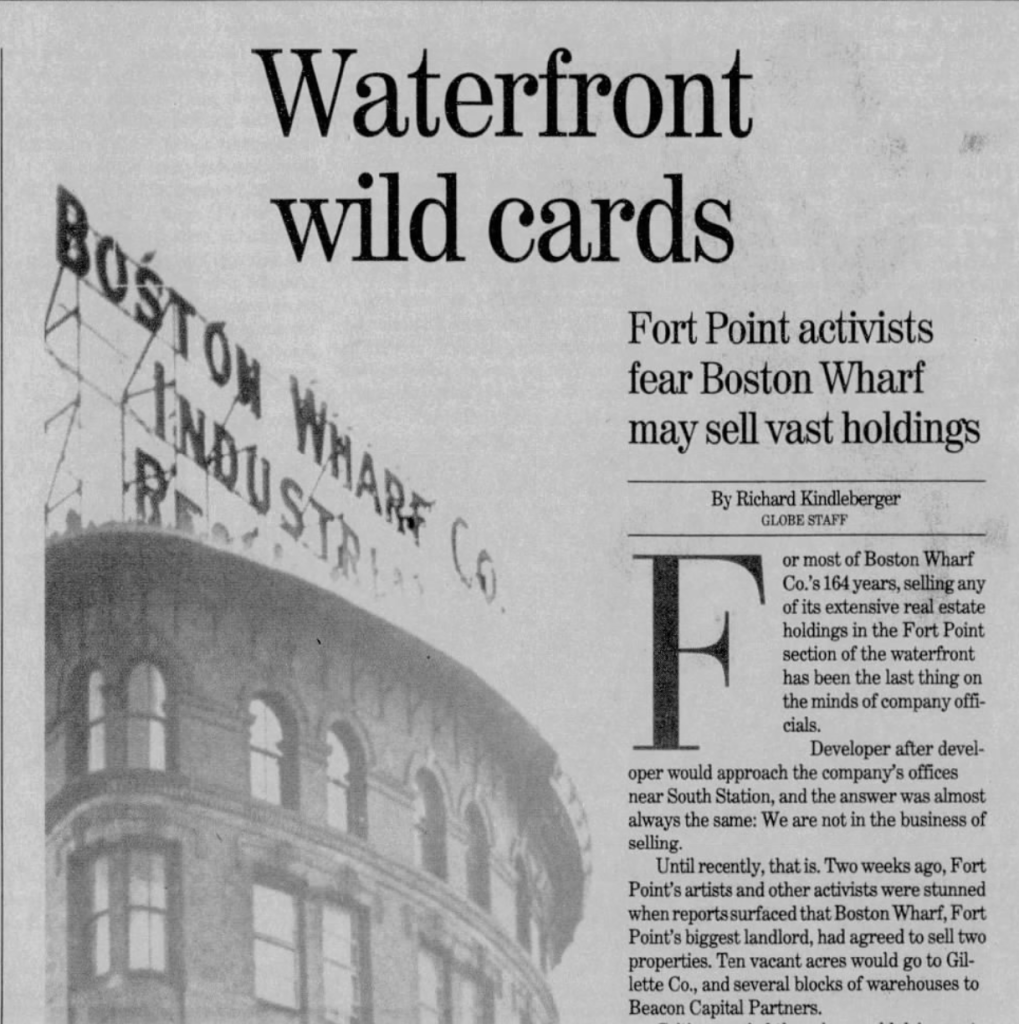

The same year, the Boston Wharf Company began selling off its sprawling holdings in Fort Point, the most consequential move since its creation of the area 150 years prior, and one that left the pioneering local artist community ‘stunned.’ The writing was on the wall; the Globe quoted a local resident and activist who feared a coming wave of development would leave Fort Point with ‘tourists on one end and a duplication of the Financial District on the other, and very little left over for a real neighborhood.’

A series of deals followed, and in 2005 the Wharf Co. sold its last tranche of properties to a subsidiary of Goldman Sachs, completing the liquidation of a portfolio that at its peak spanned 79 buildings, 30 acres, and over 3 million square feet of space. The Thomson Place site was sold to ‘an undisclosed client of HDG Mansur Investment Services Inc.’ for $92 million in 2004, flipped again in 2007 to Crosspoint Associates for $120.5 million, and in 2015 Invesco took over majority ownership in a $183.5 million deal. Invesco tapped local architecture firm Margulies Peruzzi for an ambitious ‘retail activation and streetscape project,’ and the milestones came in relatively short order: Trillium moved to its current site in October 2018, the street opened to one-way car traffic in October 2019, and the same week Trader Joe’s arrived after much speculation and anticipation. This last development in particular signaled a major evolution in the character of the street and the viability of the Seaport in general, for what ‘real’ neighborhood doesn’t have a grocery store? The developers pulled off a seemingly rare feat, making good on their goal of ‘respecting the historic context of the neighborhood while activating a new retail area for some big name tenants.’

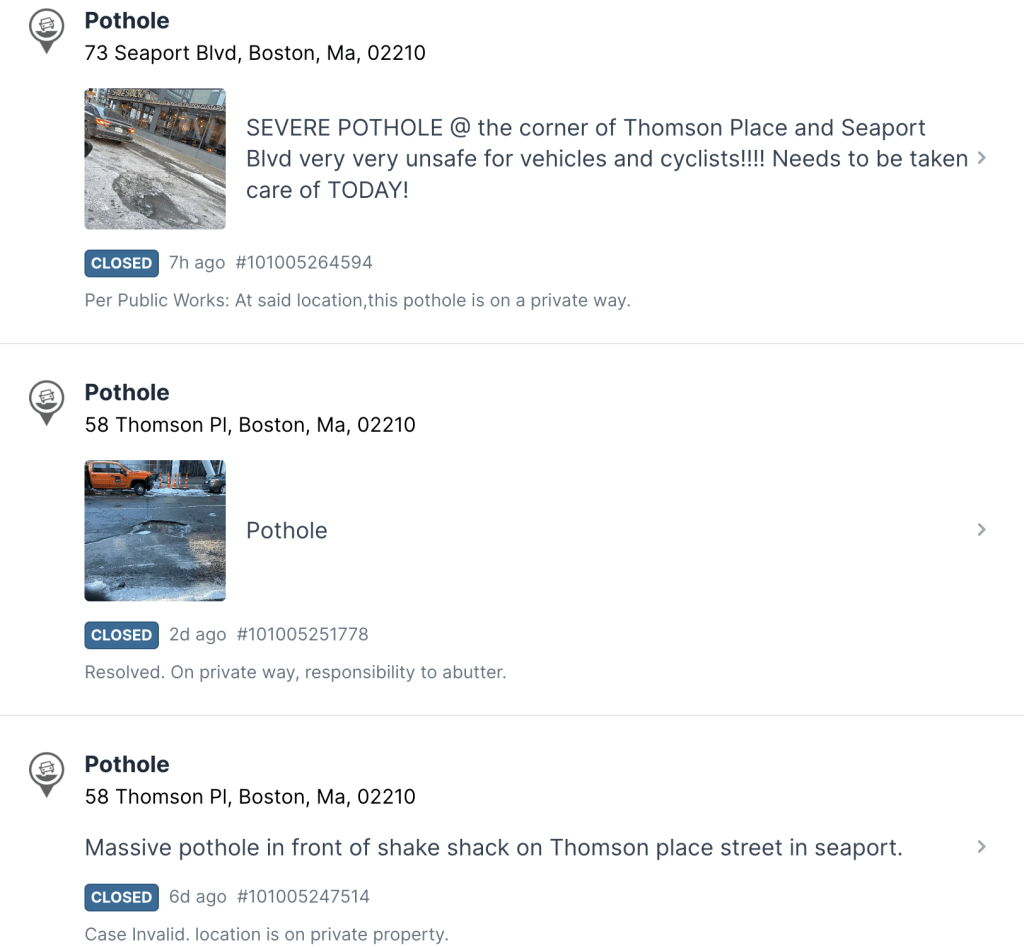

So what does any of this have to do with a pothole? Again, despite its redevelopment over the last five years as a central dining and shopping destination, Thomson Place has retained its designation as a ‘private way.’ This has important implications for street upkeep: while the ‘City of Boston is responsible for all general maintenance of public ways,’ ‘residents are responsible for all maintenance of the streets and sidewalks along the private way.’ Which is how you end up with a situation like this:

Since New Year’s Eve there have been five separate 311 reports of this specific pothole at the north end of Thomson Place between Trillium and Shake Shack, and the earliest claims that ‘It’s been there for over a year!!’ (The following sadly reports that the pothole ‘dented my rim and cost $600 to fix.’) All but the first have been closed without resolution with variations of the same response: ‘Per Public Works: On private way, responsibility to abutter.’ In other words, not the city’s problem. There’s a touch of bureaucratic absurdity to the finger-pointing that’s a little funny and a little bleak, simultaneously banal yet also symbolic of a deeper dysfunction that plagues our public places and infrastructure. That is, in the most expensive neighborhood in one of the richest cities in the richest country in the world, if we can’t fix a pothole in a well-trafficked thoroughfare, how can we possibly call ourselves serious people?

All of this is not to blame Boston Public Works nor Invesco, though we might ask for a little more conversation between both, and a higher level of attention to detail from the latter—see, for example, the misspelling of new tapas restaurant Boqueria as ‘Boqueira’ on both of the new ‘wayfinding’ signs on Thomson Place:

Rather, the point is simply to look a bit closer, and in doing so to begin to understand how the places that define our daily movements and routines came to be. Sometimes a pothole is just a pothole. This one tells a story.